“What percentage of scientists worldwide are on ResearchGate?” asked high-profile angel investor and former journalist Esther Dyson during a panel titled “European Success Story” at the DLD conference in Munich earlier this year.

Clad in a chocolate brown zip-up hoody, a grey beanie and thick-rimmed glasses, Ijad Madisch replied nonchalantly: “Sixty percent.”

Founded in May 2008 by Madisch, Sören Hofmayer and Horst Fickenscher, ResearchGate is a social network allowing scientists to upload their research, collaborate and learn from each other’s work.

Despite early skepticism about the online platform’s ability to gain traction within the scientific community, Madisch told me the professional network has garnered more than four million users. He also believes that by 2016, every scientist in the world could be a member of the professional network.

Not only that, the richest man in the world is also a backer of the Berlin-based company.

Rumours went abound last May about a looming funding round. A couple of weeks later, ResearchGate came out and confirmed a $35 million Series C round led by Bill Gates and Tenaya Capital.

Following the company’s recent launch of a new tool – which has led to an international media frenzy – I caught up with ResearchGate's CEO to talk about why the latest release is “one of the biggest things” the company has built in the last year, the competitive landscape and why making money still isn’t the number one priority...

Problems plaguing science

Before taking the helm at ResearchGate, Madisch (pictured below) – a Harvard-trained virologist and computer scientist – was on the path to become a medical professor.

However, early on, he realized changing one area of science was only a part of what he really wanted.

So Madisch put a halt to his medical research career in pursuit of another challenge – finding a way for scientists to collaborate more easily and disrupting the arcane and inefficient system of communicating scientific results.

On several occasions, he’s pointed out that a big problem plaguing the world of science is its strong focus on publishing only the positive results of an experiment.

“But in order to get to this result, you have to do a lot of research and create failed experiments,” Madisch explained at DLD in January.

He went on to say that 90% of what is created in experiments are negative results and that this chunk of data could play a significant role in accelerating scientific progress.

“I’m pretty sure if you would collect all these data sets and connect them to the right scientists in the world, we’d be much further down in treating cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, etc,” he added.

ResearchGate has already led to a number of breakthroughs. An oft-cited case saw two scientists, one in Italy and one in Nigeria, connect and collaborate through the platform resulting in the discovery of a new, deadly strain of yeast and a paper published in the journal Medical Mycology.

But the company's latest feature Open Review tackles another issue: peer review.

For a long time, another big problem with science was reproducibility – specifically whether or not research that another scientist conducted was reproducible, said Madisch.

The traditional peer review system, which typically involves a journal electing two scientists of similar competence to evaluate a paper and its suitability for publication, was put into place as an attempt to solve this problem.

“If we’re honest, the system has its flaws. But I’m thankful for the system because it’s brought a lot of successful research studies and it was good for quality control in a time when the World Wide Web (WWW) wasn’t there,” he commented.

Around the time I spoke to Madisch, the WWW had celebrated its 25th birthday. He highlighted this milestone and said that although the invention was developed for scientists, science hasn’t changed much since then.

So how does he propose to change the system?

Instead of the current pre-publish review system, which is often a slow process laced with various agendas, Madisch believes a post-review system will put scientific academic publishing on a better track.

“In order to establish this, we started with Open Review, which enables every scientist in the world to give feedback on research papers, or any sort of research output, in an environment where scientists are meeting and talking,” he told us.

Less than a month since its launch, Open Review has already sparked an international media uproar.

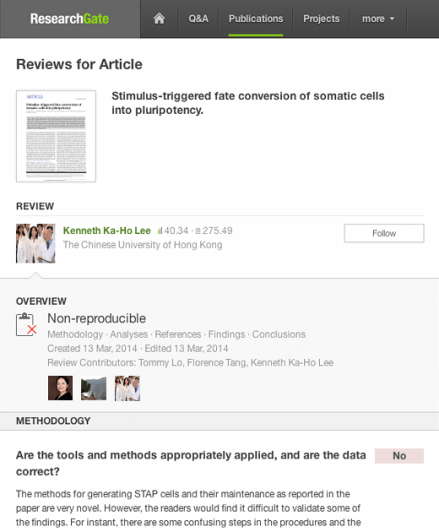

It started with Kenneth Lee, a professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, who tried several times to replicate the research of a high-profile Japanese stem-cell study published in prominent journal Nature and reported on ResearchGate that the technique doesn’t work.

"We even repeated it three times – we're quite confident it doesn't work," Lee told Wired. "If we had only repeated it once it would not have been fair on the author."

Since then, the news has snowballed into a scandal that saw Japan’s prestigious RIKEN institute accuse their own scientist of misconduct over the study. Haruko Obokata – the young Japanese stem cell scientist facing allegations – was also recently hospitalized due to her unstable mental and physical condition following the controversy.

In a matter of weeks, ResearchGate's new tool has not only provoked a conversation about the validity of a study that was hailed as a groundbreaking new way of making stem cells easily and quickly, it has unintentionally unveiled a whole new (catty) side of science to the world as well.

Even though it sounds like Open Review would largely instigate negative interaction on the platform, Madisch reassured me that there’s also a positive part to it. Namely, that a lot of good papers, which might normally be published in weaker journals because of the nature of the topic – and not the quality of research – will have the opportunity to be seen by a broader scientific audience.

“It gives the chance for scientists to also give positive feedback about papers, giving credit to what scientists create,” noted Madisch. “I think this is one of the biggest things that we’ve built in the last year and this is just the beginning.”

Science: A hotbed for startup activity

But ResearchGate isn’t the only with a vision of making science more open and collaborative.

One of the company's rivals is research management tool Mendeley, which, like ResearchGate, was also founded in 2008 by a trio of German academics.

Last year, the London-based company – which was known for committing to an open ethos towards scientific publishing – was acquired by academic publishing giant Elsevier for a reported £45 million (about 52.7 million euros).

The deal caused quite a stir in the academic publishing community with many expressing deep concern about what this would mean for Mendeley's future. Elsevier doesn’t exactly have the best record – in February 2012, over 3000 academics signed a petition to boycott the publisher over high journal prices, its position against open access to research as well as its support of anti-piracy legislation SOPA.

Only a couple of months later, news broke about ResearchGate’s massive Series C round, which included the participation of Bill Gates, Tenaya Capital, Dragoneer Investment Group, Thrive Capital as well as existing investors Benchmark Capital and Founders Fund.

When asked about what makes ResearchGate stand out from other players tackling this space such as Mendeley and Academia.edu, Madisch pointed out that quality discussion between researchers within the platform is its key differentiation.

And what does the company do to ensure this?

“You can only register to ResearchGate if you have an institutional email address – from an institution that we have white-listed,” Madisch explained. “People sometimes criticize me for this decision to only let people with a specific email address within the system, but the content is free so you could read all the discussion, papers, open reviews – that's all available.”

“But if you want to contribute, you need an email address. This one simple differentiation allows you to have a very high quality discussion within ResearchGate,” he added. “We wanted to keep the quality high and we didn’t want general comments diluting scientific content.”

Earlier this month, another competitor, MyScienceWork – a social network for researchers operating out of Luxembourg – picked up $1.1 million to expand globally and develop more products.

But, of course, not everyone is convinced. Recently, Australia’s Swinburne University of Technology criticized ResearchGate and its ilk stating:

These sites rely on you uploading your papers to build their content base, so they don't provide you with much information on what you can and can't upload. They rely on you reading and understanding your publisher agreement to know which version (if any) you can post.

The overall message? Proceed with caution.

Making money still isn’t the number one goal

Although ResearchGate seems to be on a healthy trajectory, turning a profit still isn’t a main priority, Madisch told us. This sentiment is something that he has stressed time and time again.

“Our monetization strategy is something that is still secondary. It’s something, of course, we’re now starting to experiment with it, especially with the recruiting product. Every monetization strategy we have on our list is aligned with the goals of the community. We’re not building something to squeeze information out of the scientific network or to misuse data,” he elaborated.

The recruiting product is simple and it involves universities and companies posting open positions onto the platform for free. He said that ResearchGate would only receive payment if the job was featured on specific pages on the site for better targeting.

“Focus number one is still product, growth and helping the scientific world make progress,” he said.

Matt Cohler, general partner at American VC firm Benchmark Capital and early Facebook employee, is likely part of the reason why Madsich holds so strongly to this mentality.

When Cohler joined the company’s board at its Series A stage, he advised the ResearchGate CEO to forget about revenue until the network was valuable enough to command it.

Interestingly enough, rival Mendeley is also in a similar position. Now that it’s part of Elsevier, the company has no particular timeline for profitability and is also focusing on user growth and engagement.

Though it may not be a priority, making money is still in the cards and many are keen to see how these companies will eventually maintain a fine balance between mission and monetization.

The roadmap for ResearchGate

Headquartered in Berlin with an office in Boston, ResearchGate has now grown to around 120 employees hailing from across the globe – so what’s next?

“I don’t know. I usually don’t plan more than three months into the future,” he responded honestly. “Even if we did have plans for the next three months, it could all change in two weeks.”

For ResearchGate this works, he said, because the team is "very agile and can change direction pretty fast if we see something which we have to do”.

But one thing he does know for sure: “Selling the company, for ResearchGate, would be a failure.”

“We want to build something very fundamental, which changes science. This is something we have to do on our own and not with someone else,” Madisch added.

In a recent interview, Bill Gates spoke about innovation in California and said:

Sure, half of the companies are silly, and you know two-thirds of them are going to go bankrupt, but the dozen or so ideas that emerge out of that are going to be really important.

A few days later, a comprehensive piece was published in the New York Times chronicling Silicon Valley’s Youth Problem.

For me, one of the key questions addressed in the article was: "Why do smart, quantitatively trained engineers, who could help cure cancer or fix healthcare.gov, want to work for a sexting app?"

Since ResearchGate (alongside SoundCloud) enjoys a lot of attention and is often heralded as a success story for Berlin’s startup scene, I was interested in hearing Madisch’s thoughts on why/how smart, qualified engineers capable of tackling the world’s most pressing problems frequently end up working for Another Frivolous App.

“It’s the serious issues – if you want to solve them – that are always more complicated... Sometimes it’s just easier to follow an easier path,” he answered matter-of-factly.

“I always say this to developers when we hire them, ‘Here, your code is changing something and if you want this and have this ambition, then be part of an amazing journey’. But I don’t want people who just do it for the money.”

For more tech.eu content, please subscribe to our weekly newsletter, on Twitter and on Facebook.

Featured image credit: wavebreakmedia / Shutterstock