What would €1.5 trillion look like? I asked ChatGPT. Without hesitation, the all-knowing oracle spat out:

“A stack of 100-Euro bills would reach over 42 times the distance from the Earth to the Moon.”

Well, that’s what Europe is leaving on the proverbial table every year, according to a recent study by Accenture. And the root cause, you guessed it, is the “tech deficit.”

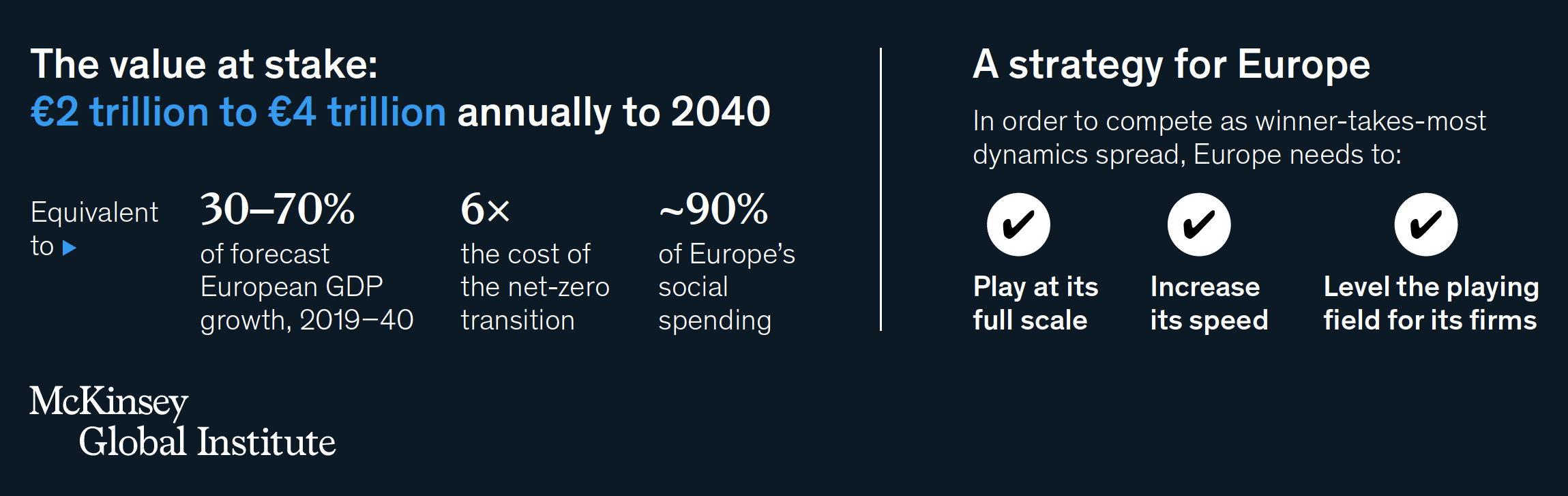

Another groundbreaking research by McKinsey suggests that €2-4 trillion a year of corporate value added could be at stake by 2040 if European economies fail to close the gap on transversal technologies. These are, essentially, cross-cutting tools with the potential to transform multiple industries: think electricity, telegraph, and a steam engine.

The good news is that this disruptive, productivity-boosting type of tech is the best hope Europe and the rest of the world have to address humanity’s most complex challenges like global warming, public health, or labor productivity in the era of rapid population aging. The bad news is that Europe, which had phenomenal success with transversal technologies in the past, is now struggling to keep up.

Accenture’s blunt counsel – innovate or fade – is a wake-up call. But this dire warning hides an upside. A growth dividend awaits Europe if we find a way to address the tech deficit, defined as “disparity in adoption, implementation or effective use of technology (both established and leading edge) to create business value.”

This isn’t a question of investment in technology or R&D spending by corporations or governments alike. It's about global tech leadership, at least in some key areas, deployment of truly digital business models, and the ability to turn them into added value.

Europe’s conundrum

The European Union is home to the world’s most decarbonized economy. And, notably, the continent leads the world in various rankings and metrics, be it Human Development, Social Progress, Genuine Progress, or even work-life balance.

While these accomplishments command respect, they do not address the resilience of Europe's economic competitiveness. The latter is the foundation on which our quality of life and climate stewardship rest. And it is the technological ascendancy that is central to Europe’s future economic prospects if we accept McKinsey Institute’s argumentation.

Regrettably, the continent’s performance on transversal tech registers somewhere between subpar and woeful. We are talking about 30-70 percent of Europe’s forecasted growth in the coming decades of corporate value-added that Europe might fail to create.

The startup scene

2021 was one of the best years for tech startups in recent memory. According to Atomico, Europe saw the number of unicorns soar, and it bested China with a record $106 billion of venture capital funding. While this figure is quite impressive, it was just a third of the US’s. And worse yet, we’ve not seen sufficiently large companies emerge from the investments to deliver discernable impact on Europe’s overall corporate performance.

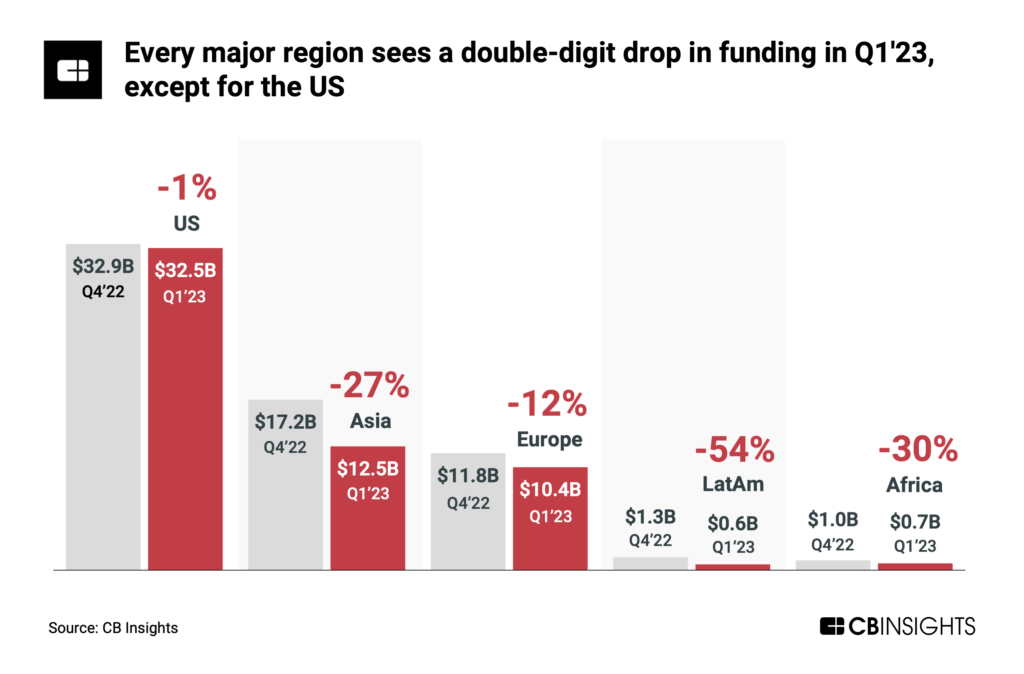

Between 2020 and 2021, startup funding in Europe more than doubled. The number of deals, too, was following a steady upward trajectory. But the surge didn’t last; the global venture ecosystem has shifted into the reverse gear in 2022-2023. This doesn’t bode well for Europe, which is playing catch-up.

In the first quarter of 2023, almost every region of the world saw double-digit drops in capital flows towards startups, CB Insights reported. Venture funding in Asia fell by 27 percent from $17 billion in Q1 of 2022 to $12.5 billion in Q1 of 2023. Europe’s fell by 12 percent but from a smaller base of $11.8 billion to $10.4 billion. In the US, however, the funding level held steady eclipsing Europe and Asia combined, going from $32.9 billion to $32.5 billion.

Corporate underperformance

Whether the startup ecosystem is healthy or struggling, let us not conflate it with innovation-driven economic competitiveness. Locally grown unicorns are the pieces of the puzzle, not the puzzle itself.

Europe’s underperformance is most visible when it comes to major corporations. And it makes for a dreary reading. In 2000, large European firms were valued on par with their US peers ($7 trillion versus $8 trillion). By 2021, however, the ratio was 2-to-1 in the US favor ($46 trillion versus $21 trillion). Large European firms are adopting AI at half the speed of their Chinese counterparts. It’s the same story for quantum computing: none of the world’s top ten companies are headquartered in Europe, and public funding is only half that of China.

Large global European firms are growing 40 percent more slowly than their US counterparts. They’re investing 40 percent less in R&D and are now 20 percent less profitable.

This isn’t a question of market valuations or corporate profits. If left unaddressed, this tech deficit and sluggish corporate performance will erode Europe’s climate leadership, economic competitiveness, and comparative geopolitical weight.

European tech champions. Where are they?

In a resonant piece for the Financial Times, Gideon Rachman points out that U.S. tech giants like Amazon, Microsoft, and Apple dominate the European landscape. The top seven global tech firms by market capitalisation are American, with only ASML and SAP representing Europe in the top 20.

What’s so crucial about large players in tech? Doesn't innovation happen at startups? Isn’t it better to have many medium-sized companies rather than a few large ones? Those are interesting questions to ponder, but in the age of AI, datasets trump algorithms. As ChatGPT put it to me:

"Algorithmic elegance without data is like an F1 car without fuel."

To have global relevance, a tech enterprise needs a global scale.

And that brings me to a European digital champion I know well – Booking.com. For years, we’ve invested significant resources in AI development, with around 400 employees working on AI-related projects – software engineers and data scientists – primarily at our headquarters in Amsterdam.

We collaborate with local colleges to keep current with the latest A.I. research and, in 2021, launched Mercury Machine Learning Lab in partnership with the University of Amsterdam and the Delft University of Technology.

This type of collaboration is essential for Europe to remain competitive on transversal tech. After all, AlphaFold, which “predicts 3D models of protein structures and is accelerating research in nearly every field of biology,” is a direct descendent of AlphaGo – an AI trained to play a board game. In the same vein, the troves of data we’ve collected over the years in the low-risk space – matching travel demand with supply – could help train new AI models, be it in cancer research or green energy.

What to do?

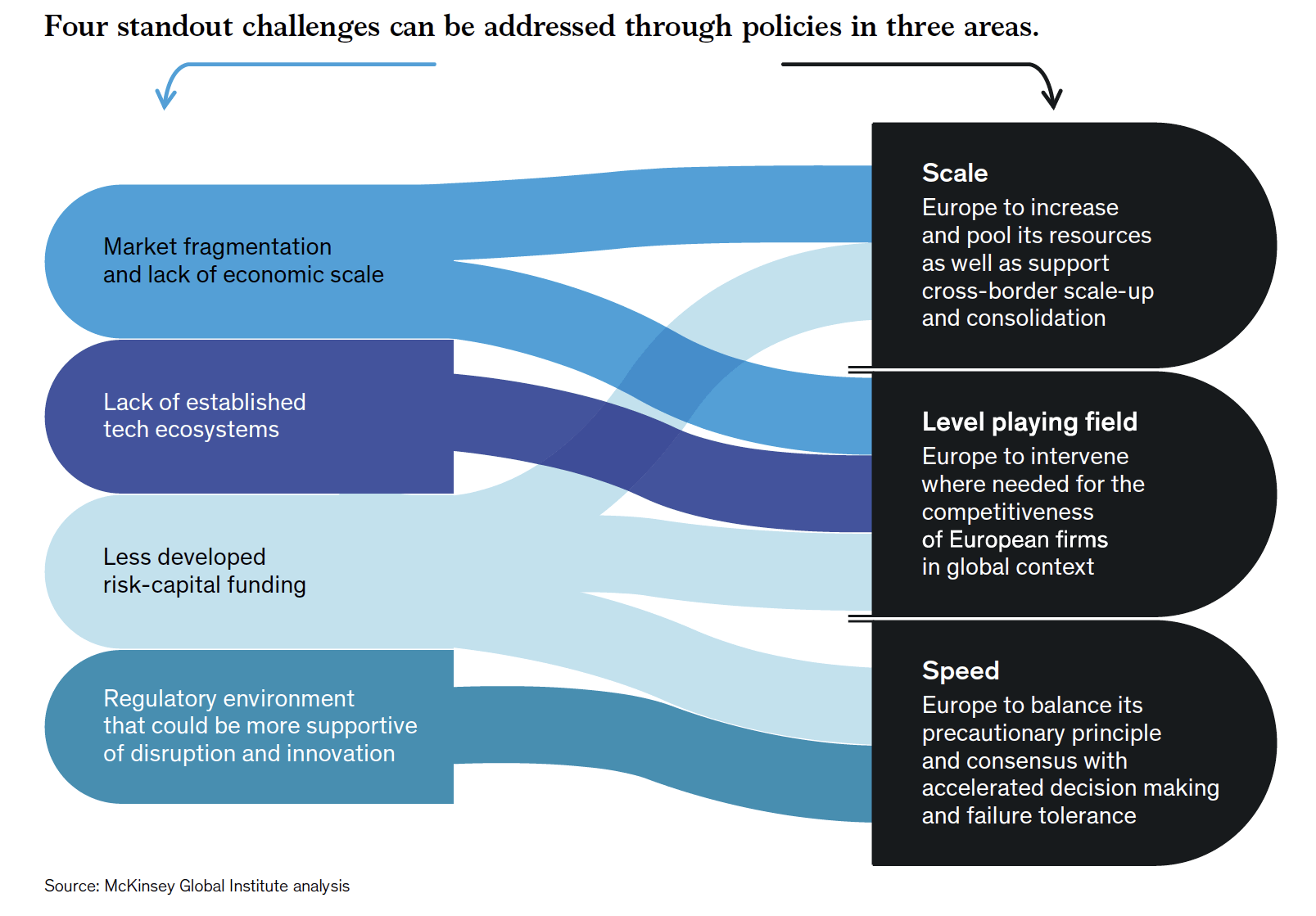

McKinsey Institute identified four mutually reinforcing features distinctive to Europe: “fragmentation and lack of scale; lack of established technology ecosystems; less developed risk-capital funding; and a regulatory environment that could be more supportive of disruption and innovation.” The latter is easier said than done, but a starting point has to be an acknowledgment that a big player in tech could be a positive force for European competitiveness and no amount of startups could compensate for the absence of global champions.

In a recent article, the Economist magazine urged its readers to consider Joseph Schumpeter’s perspective:

“Big firms—monopolies, even—that drove innovation, thanks to an ability to splash cash on research and development and quickly monetise breakthroughs using existing customers and operations, spurred on by a constant fear of being toppled.”

Brussels’ regulatory superpower aspiration is merited when it comes to consumer protection and safety online. Still, even a minor miscalibration could lead to serious unintended consequences – accelerating the slow-motion corporate and tech crisis McKinsey spotted over a year ago.

One risk is to deprive European consumers of access to the world's innovation, but perhaps a bigger one is to erect barriers for local firms to achieve global scale. Europe gave birth to the 1st Industrial Revolution, and now it must find a way to master the 4th.

Lead image: AXP Photography

Would you like to write the first comment?

Login to post comments