The butterfly effect is a well-known pillar in chaos theory and its premise that the simple flapping of a butterfly’s wings in China can cause hurricanes in Texas has had huge cultural influence.

It is cited in any number of films including Back To The Future and, more poignantly for this article, AI’s favourite (and lazy) touchpoint Terminator.

One of my lowlights this year was attending a UK House of Lords session where the presentation continually cited Arnold Schwarzenegger's film as why the UK was leading the way in AI. More like AI for Idiots.

However, there are other places outside the UK Parliament where more enlightened people are setting the standards for the future of AI (and humanity for that matter) with frameworks that will resonate far from where they were announced… not least in Europe.

Europe has spent the past decade wrestling with the contradictions of its tech ambitions: yearning to lead in innovation while regulating with an iron fist, chasing Silicon Valley while side-eyeing it and insisting on “strategic autonomy” while relying on US cloud providers and Asian hardware.

So when a new global declaration on AI emerges, this time via Seoul in South Korea, it’s worth asking not just what it means for global governance, but what it means for Europe that desperately wants a seat at the top table of AI rule-making.

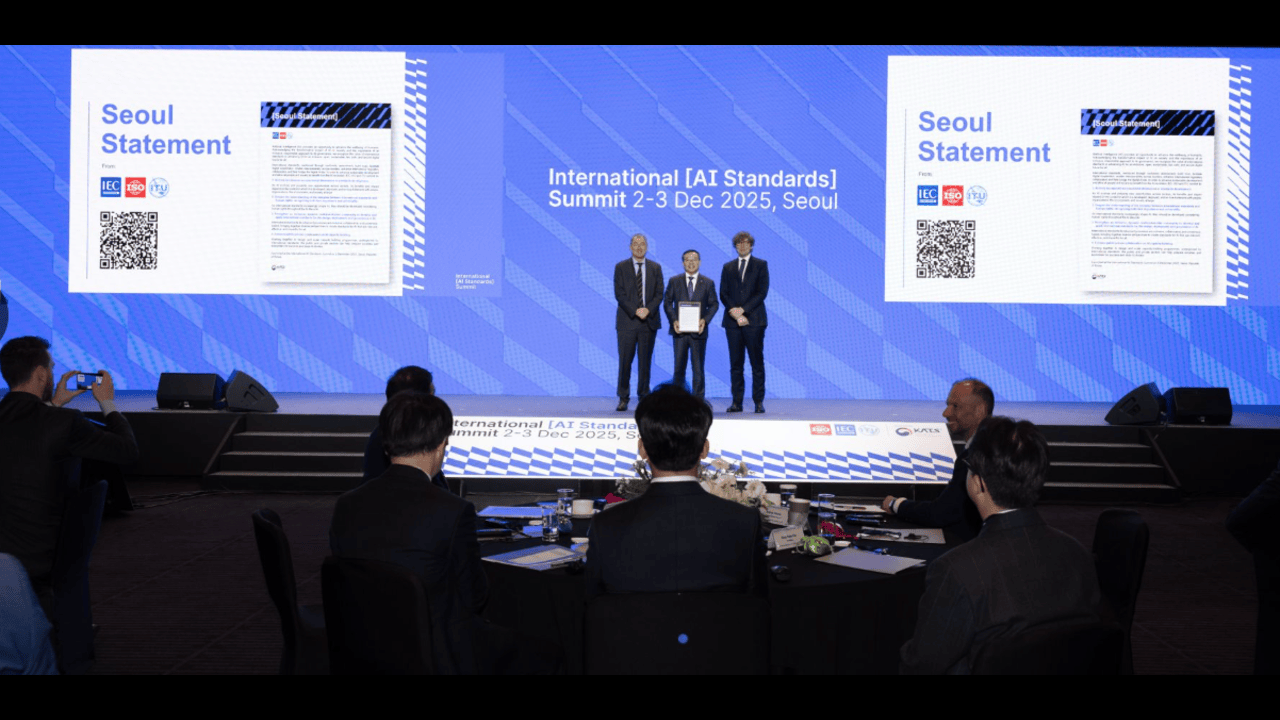

The Seoul Statement, announced last week at the inaugural International (AI standards) Summit in South Korea, is the latest in a string of international overtures attempting to corral AI into something safer, fairer and more widely beneficial.

In front of a personally invited audience of 300 people, it framed AI as ‘an opportunity to advance the well-being of humanity’ and emphasised an ‘inclusive, open, sustainable, fair, safe, and secure digital future for all’.

Vimal Mahendru is the IEC Vice-President and Chair of the Standardization Management Board and was in Seoul to witness the announcement.

“It is always about people, about making technology work for all humanity, and not the other way around. Amidst rapid technological developments, the Seoul Statement aims to safeguard our shared future by placing the aspirations of all humans at the centre of AI governance and standards development,” he said.

Europe, meet the world (finally)

For once, the global AI conversation sounded very… European. The Statement stressed socio-technical contexts, how AI behaves not in the lab, but out in the wild, interacting with people, institutions and societies. It’s as if the world has been reading EU white papers on long-haul flights and decided they make sense after all.

But this isn’t just a pat on the back for Europe’s regulatory evangelists. The Seoul Statement also lands at a moment when the EU is staring down the reality that rules alone won’t build AI champions. Europe is still over-indexed on governance, under-indexed on compute, and chronically under-funded compared to the US and China. Aligning with global standards matters, but only if Europe can engage from a position of technological strength, not moral superiority alone.

Standards: the Brussels effect meets the Seoul effect?

The Statement gives international standards pride of place, arguing that they ‘build trust, facilitate digital cooperation, enable interoperability across borders’ and strengthen regulatory collaboration. What’s interesting is that Seoul now positions standards as a tool not just for safety or accountability, but for development and inclusion.

As Mahendru continues:

Building on the work of the Council of Europe's framework on Artificial Intelligence, Human Rights, Democracy and the Rule of Law, the statement highlights the role that international standards play as part of a holistic approach to AI governance. “By making the connection between technical standards and human rights in this way, we have taken an important and necessary decisive step towards ensuring that transformative technologies like AI work for the good of society.

Europe should pay attention to Mahendru’s words. Because while it has historically exported rules outward, AI is exposing its own internal divides: between data-rich and data-poor industries. Between countries with powerful research ecosystems such as France and Germany and those still digitising basic services in parts of Southern and Eastern Europe, between startups leveraging frontier models and SMEs still figuring out cloud migration.

If the EU wants to remain relevant, it must consider standards not as a cudgel, but as connective tissue, something that keeps Europe interoperable with the rest of the world, prevents digital isolation and ensures European AI remains compatible with global markets.

The multistakeholder moment

The Statement emphasises building a ‘dynamic multistakeholder community’ for AI standards, one that is ‘inclusive, collaborative and consensus-based’.

That may sound obvious, but it’s a subtle rebuke to the more top-down approaches emerging elsewhere. Europe has always prided itself on ‘multistakeholderism’, even if it sometimes forgets to invite stakeholders who aren’t regulators.

The Seoul framing presents an opportunity for the bloc to rebalance: to ensure industry, academia, civil society, and, crucially, small companies and scale-ups have real influence in shaping how AI is governed internationally.

Because while European corporations are well represented in standard-setting bodies, its startups often are not, and yet it’s the startups that will feel the effects most acutely.

The global stage is shifting. Europe can’t just spectate.

The Seoul Statement is part of a broader geopolitical rebalancing in AI. Leadership is no longer purely a transatlantic affair. South Korea, Japan, Singapore, the UAE and others are increasingly setting the pace, not just in technology, but in how AI is governed.

Europe cannot assume that its frameworks will automatically become global defaults. It must engage deliberately, diplomatically and with humility.

It must show up to standards bodies early, not late. It must ensure its safety narratives are backed by technical expertise, not just legislative brilliance. And it must invest in the infrastructure and talent that make participation credible.

The bottom line

The Seoul Statement echoes Europe’s values, but it also exposes Europe’s vulnerabilities. Alignment on paper is easy; influence in practice is earned.

If Europe wants to remain the moral conscience of AI while also becoming a technological heavyweight, it must treat international cooperation not as a validation of what it has already done, but as a challenge to do more… and to do it faster.

Because the future of AI will be shaped by those who build it, those who govern it and those who set the standards that sit between building and governing. Seoul is inviting Europe to help lead that middle ground.

Would you like to write the first comment?

Login to post comments