It’s a pretty familiar story in techie circles; everyone seems to know at least one entrepreneur that has tried to set up shop in another country and has struggled to do so because of the oh-so-complicated visa application procedures and hefty requirements.

In recent years, it's become a bit of a new trend for governments to introduce so-called entrepreneur or startup visas. Despite all the talk of facilitating immigration for foreigners who want to create jobs and can secure a minimum investment, only a handful of countries have actually put a specific entrepreneur or startup visa into place - including the UK, New Zealand, Singapore, Canada and a handful of others.

In Europe, there has definitely been a lot of talk about entrepreneur visas, but sadly it's mostly just that.

So far, only two countries have clearly defined visas for entrepreneurs: the UK and Ireland. While other countries, including Germany and France, have in recent years developed new visas for people setting up a business, these visas are not designed strictly for startup entrepreneurs.

The UK has clearly been the most innovative and forthcoming, having introduced three different entrepreneur visas ahead of the curve in 2011. These include visas for 'prospective entrepreneurs' (founders seeking funding), entrepreneurs and 'graduate entrepreneurs'.

While each of these visas seems potentially well adapted to the three different types of entrepreneurs identified, there are clearly some shortcomings - specifically the funding requirement of either £50,000 from a registered VC or seed fund competition. As many founders will attest, VC and seed competition awards of £50,000 or more are limited in Europe, even in the UK.

Besides, last I checked, entrepreneurs tend to make better business decisions when they're not sitting on a wad of £200,000 - though I could be mistaken.

The graduate entrepreneur scheme in the UK, which had a rather high acceptance rate of 88 percent during the last year, received an incredibly low number of applications during its first year – only 135 candidates for the 1,000 visas available. Regardless, an additional 1,000 visas were made available annually for this category (up to 2,000 per year), which can now be allocated through registered universities themselves.

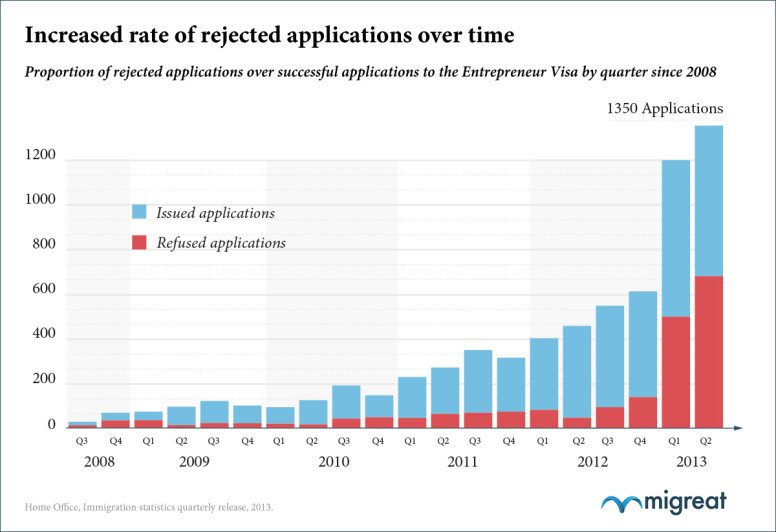

While the UK has done a fabulous job at developing and communicating the existence of these different visas, it has unfortunately struggled to keep up with demand. At the end of September 2013, the Home Office revealed a backlog of 9,000 applications and was taking over eight times longer (63 days) to treat each request than initially planned.

With different sources revealing refusal rates between 50 and 75 percent, it's not even very clear how many applicants are actually making the cut.

Given that the government also changes visa rules and availability rather frequently (recently not-so-immigration friendly with foreign taxpayers, according to The Economist), it's difficult to tell whether or not this is really having much of a positive impact beyond marketing.

Britain tends to get the most attention for its entrepreneur visas in Europe, but Ireland's visa - known as the "Start-up Entrepreneur Programme" - should not be left out.

Established by the Irish government in 2012, qualification initially required entrepreneurs to show a whopping 300,000 euros in the bank, the possibility to employ 10 people and reach 1 million euros in revenue within the first 3 to 4 years. Arguably, not your average startup.

Fortunately, the government later went on to reduce this amount to 75,000 euros and has since grown more relaxed on job creation and revenue requirements.

Somewhat similar to Ireland, Germany established an entrepreneur visa with a "recommended" investment of 250,000 euros and creation of at least five jobs, which it lightened in 2012 at the same time that it introduced the EU Blue Card, Europe's self-proclaimed "answer to the US Green Card".

France has a similar visa that has been in place for several years, although more recently the country has said it will introduce a new entrepreneur visa and even a special "digital pass" for Web entrepreneurs in 2014.

Not much more information has been provided over the last few months regarding visa quotas, investment or job creation requirements, however, which means we can't really be sure what the French government's plans are at this point.

The aforementioned EU Blue Card scheme, which aims to turn Europe into a more attractive place for skilled foreigners to work, has also been pretty effective.

Currently, all EU member states except for the UK, Ireland and Denmark are part of the EU Blue Card network.

Still, application requirements vary slightly from country to country, and applications can take up to several months to be examined.

Startups wanting to hire foreign talent cannot always afford to wait for the application to go through and therefore may opt for someone less qualified but local, thus potentially harming their business in the long run or at least stifling its potential for faster growth.

All this matters for a startup's 'exit potential' as well. Guillaume Lautour, a partner at French VC firm Idinvest Partners, finds that often a foreign management team can make a company more attractive for an acquisition, for one. Having Americans in the management team of a French company may make it a more likely candidate for acquisition by an American firm, he argues.

When it comes to entrepreneur visas, Europe isn't very different from the US, which may sound reassuring - but it really isn't.

Fortunately, Europe has examples like the UK to show that some governments know how to recognize the benefits of foreign entrepreneurs for the economy.

Still, even the best attempts are often criticized because of the somewhat ridiculous investment and job creation requirements, waiting period and heavy administrative burden - all of which are very entrepreneur-unfriendly and don't take into account the agility needed when first starting a tech startup that's meant to scale more quickly than your average small business.

That said, Europe definitely has a lot to gain by making it easier for entrepreneurs to immigrate and do business on the continent - and to hire internationally. European countries should look at introducing several different entrepreneur visas available for different types of projects and profiles of entrepreneurs.

But, more importantly, governments should also look at involving local entrepreneurs and the ecosystem in selecting projects and visa procedures that would be more relevant for incoming talent.

Featured image credit: Christophe Testi / Shutterstock - hat tip to Josephine Goube for the visuals.