This article originally appeared on Hackernoon on October 13th 2022 and is reprinted with author Chris Chinchilla's permission. Note that the events described in this post took place before the recent ramp up from Russia in the war in Ukraine.

I have been to many tech conferences over the years. I have sat in so many startup pitches and talks that are barely masked marketing pitches. I have introduced myself and told people what I do and where I am from so many times that it all becomes something of a blur.

Despite the repetition and occasional tedium, I still enjoy attending these events, especially after the best part of a two-year absence. There’s the opportunity to meet new people, and visit new places, and typically amongst the familiar and tedious talks and pitches, there are shining gems to find. And those moments make it all worthwhile.

This was my third invitation to attend IT Arena in Lviv, Ukraine. But this was the first time, and indeed a first for me overall, that the conference happened during a war and in what was effectively a warzone.

Lviv is far from the front lines in the conflict, and checking with locals and experts, considered relatively safe, but still, despite this being my third visit, so much was different.

Crossing the border from Europe into Ukraine was generally fairly easy when flying in the past. This time, after a long drive from Krakow, the border crossing wasn’t as bad as I had imagined. It wasn’t that busy, just lots of waiting around. Hand your passports to a Polish official, and they wander off somewhere and come back later with them. Then cross to the Ukrainian officials who also take your passports, ask why you’re here, and then return with them sometime later. Then after a lot of hanging around, off you go again. I was amused to see they stamped my entry date neatly below my last pair of stamps from a 2021 summer trip to Odessa. Almost like a sort of “good to have you back” gesture.

The road from the border to Lviv is narrow but vastly improved from the last and only time I had driven around the area. Apart from the surface having improved, the sides of the road are adorned with posters telling people to sign up for the armed forces, bold and smiling soldiers staring down as you pass. There was the occasional outpost along the road, sandbags, and “Czech hedgehogs” lying unattended at regular intervals, I guess, should the need arise to use them. Finally arriving in Lviv in the early evening, it hit us all how dark the city was. The street lights were off, whether to save money or for security reasons, we weren’t sure. Despite the darkness, the streets were busy and teeming with people. There is a 23:00 curfew, with all places closed by 22:00, so after work, there’s a lot to fit into the time available. After a long journey, we checked into the hotel and rushed to find one of the handful of restaurants that stayed open an hour later and caused the first of many surprises when the staff heard we weren’t Ukrainian.

We returned to the hotel and saw a young musical duo playing in the middle of the wide Svobody Ave. They seemed to be playing songs familiar to many of the other young onlookers, who shouted and danced along to songs that were unfamiliar to us. Strangely it all reminded me of my Grandmother’s tales from living through the London blitz in WW2. Even during times of war, people still need to find ways to enjoy themselves and celebrate life as much as possible.

Day one - Startup competition

For day one, there were two venues for IT Arena. In the morning, it was !FESTrepublic, an old power plant with numerous sprawling buildings spread across the site, mostly now converted to restaurants, event spaces, and the brewery for the famous Lviv Pravda beer theatre.

After hours of sitting on a bus the previous day, we walked to the venue through Znesinnya park. It was heavy with mist, adding a surreal quality to the path dotted with small altars and crucifixes.

When I first came to Ukraine and IT Arena around five years ago, there was the general feeling that while Ukrainians are highly skilled technically, they were (among some other things) lacking in communication, marketing, and pitching skills. This has improved every subsequent time I have visited, and while some of the pitches this year were a little rough around the edges, the quality and ability of presenters to tell a compelling story was vastly improved. Typically the main problem for the presenter was that they had to pitch in English, which increased the effort needed. I was pleased to see that the judges asked tough questions, and while they often tripped up the presenter, their enthusiasm and energy never waned. Energy and enthusiasm are traits that always attract me to eastern European events and projects, and it was unrelenting around the venue. Noticing I wasn’t local, people would often approach me, asking to tell me their idea or connect on LinkedIn. Someone was always on a video call pitching to someone else somewhere in the world or conducting business.

Most of the startups in the final for the competition were typical B2B or B2C ideas, but a handful focussed more on solving local problems that could expand to a global reach, for example, health care. A pitch that stood out to me was “Wrap”, a platform designed for planning film projects. After recently collaborating on a two-day broadcast organized ostensibly through spreadsheets, I could see the need. They did win :).

You can find the full list of semi-finalists on the IT Arena website.

After the finalists had pitched, the event moved to the opera house in Lviv city centre, a grand old building with three levels of seats. As with many old buildings in the city, the windows were boarded up, and sandbags were also filling any ground-floor windows. Also, like many other buildings, any basement layers had been hastily renovated and reclaimed as bomb shelters.

In addition to the younger IT Arena staff and volunteers at the venue were the opera staff, a fleet of elderly ladies who are a familiar sight in eastern Europe. We had no idea what they attempted to say to us, but as we arrived late, they ushered us through a secret room into the Opera’s private box closest to the stage.

The opening ceremonies started with a discussion on how charitable donations, philanthropy, crowdfunding campaigns, and volunteering have helped support Ukraine so far.

The evening ended with a performance from Antytila, a band described to us by locals as one of the most popular bands in Ukraine. They hadn’t performed since the war began, and some of the band members had been on the front lines, where they also took footage they used in videos projected behind them as they played.

The band finished, and we rushed out into the night to find dinner before curfew.

Day two

Looking down the program of talks for day two was a different experience from many events I've been to before. There are none of the usual talks, and I can't imagine many events I'm likely to attend in the near future that will discuss issues such as these. Alongside the typical startup event crowd, there are senior outsourcing company staff mixing with government ministers, cybersecurity experts, and weapons experts.

It's a heady mix that generates intense discussions I'm still processing and forming opinions. I'm fundamentally a pacifist, and it's an odd feeling to hear frank conversations about war and how to fight and survive one and kind of be onside with and supportive of those discussions.

There's a lot I could cover, and maybe I will in more detail in the future, but here's some of the main themes and points.

Government, society, and technology working together

The current conflict has provided one of the few examples of technology experts and businesses working swiftly and effectively in unison with the government. Granted, the current Ukrainian government is relatively new, young, and full of people fresh from outside professions. The technology industry in Ukraine is a mix of outsourcing companies working on contracts for companies elsewhere and rapidly emerging and scaling startups building products, also largely for overseas audiences. Still, the speed at that they managed to relocate employees and adapt to working environments and needs was astounding.

The panelists spoke about how they did and still do, need to reassure foreign customers and investors that business continues mostly as normal, what to expect moving forward, and when there might be temporary delays and problems in delivery. So far, it seems that those foreign customers have been nothing but supportive.

Many times in the discussion, the panelists commented on how the COVID-19 pandemic-induced lockdowns were a rehearsal on rapidly shifting working patterns. And in recent history, with events such as the revolution of dignity and the annexation of Crimea, Ukraine has been here before and had to manage work during periods of rapid change. There were numerous times when I realized that the revolution of 2014 was only eight years ago and marveled at how far the country had come since then.

The adaptations didn’t just come from Ukrainian sources but also with help from outside. Many cited the effectiveness of the Starlink rollout in keeping the country well-connected at a time when effective information pathways are more crucial than ever.

One of the most challenging aspects of managing the ongoing conflict has been striking a balance between sending enough people to fight as soldiers and having enough working to keep the economy (one which wasn’t the most stable before) running.

So far, the system is maintaining that balance reasonably well, with men called to join periodically for several months of service and anyone also welcome to volunteer. According to research from the Lviv IT cluster, at any one time around 5-13% of any company’s workforce are mobilized at one time, with 5-43% of the workforce expected to be mobilized at some time. The ranges are broad as the percentage impact depends on the size of the workforce. Some businesses continue to pay employees when they are on service.

You can read the full report Lviv IT cluster’s website.

Those called up can return for special exceptions, and we did see many returned men in army uniforms home wandering around Lviv with family and friends. There are also exceptions to the call-up, but it wasn’t clear to me exactly what these were. One of the main issues for Ukrainian working men was those needing to make business trips. They are currently allowed out of the country for seven days. The only options for long-distance travel right now are trains, buses, and cars. Crossing borders between Ukraine and elsewhere takes a long time, around three days, which means that while trips to Europe are just about possible, the US, Asia, and Africa typically aren’t. There is talk of this changing soon, but I did wonder if other industries were afforded these same luxuries in a time of conflict. The technology industry in Ukraine is a big contributor to the economy and likely the future of the country. I am sure there are others just as important, and I got the feeling there was a little resentment from some of the population to the privilege of the technology industry. Ukraine is still a poor country full of financial extremes and disparity, and as anywhere else, it’s easy to be lost in the technology bubble.

It seems and feels like the war is cautiously turning in favor of Ukraine, and while it may be too early to ask these questions, myself and others started wondering, what happens afterwards? Will the close working ties between government and business remain? Panelists discussed that “when this over” (with a general feeling of “in Ukraine’s favor”) the plan is an ongoing refocus on entrepreneurship and less on outsourcing. Is this a good idea? Startups are not the be-all and end-all and can easily fail, especially as we move into a time of economic uncertainty and a potential end to easy investment. Before this period of conflict, Ukraine was enjoying a period of easier working visa requirements with Europe, which meant many skilled individuals were leaving the country. Will this trend continue? Or will more want to remain home to help rebuild?

Finally, the panel discussed what would happen to those returning from the front line. How would the country reintegrate them into society with meaningful work and opportunities? Some cited programs in the USA, but from my limited experience and exposure, it has always seemed that many countries, the USA included, treat veterans fairly poorly. I guess much of it depends on how long the war lasts.

Perhaps the most important message to the audience in the room and wider was the importance of investment, not charity. As the country rebuilds, it will need a lot of help from elsewhere, but it wants to emphasize that it needs that help mostly in the form of new contracts and new opportunities.

Insights from Russian cyber tactics against Ukraine

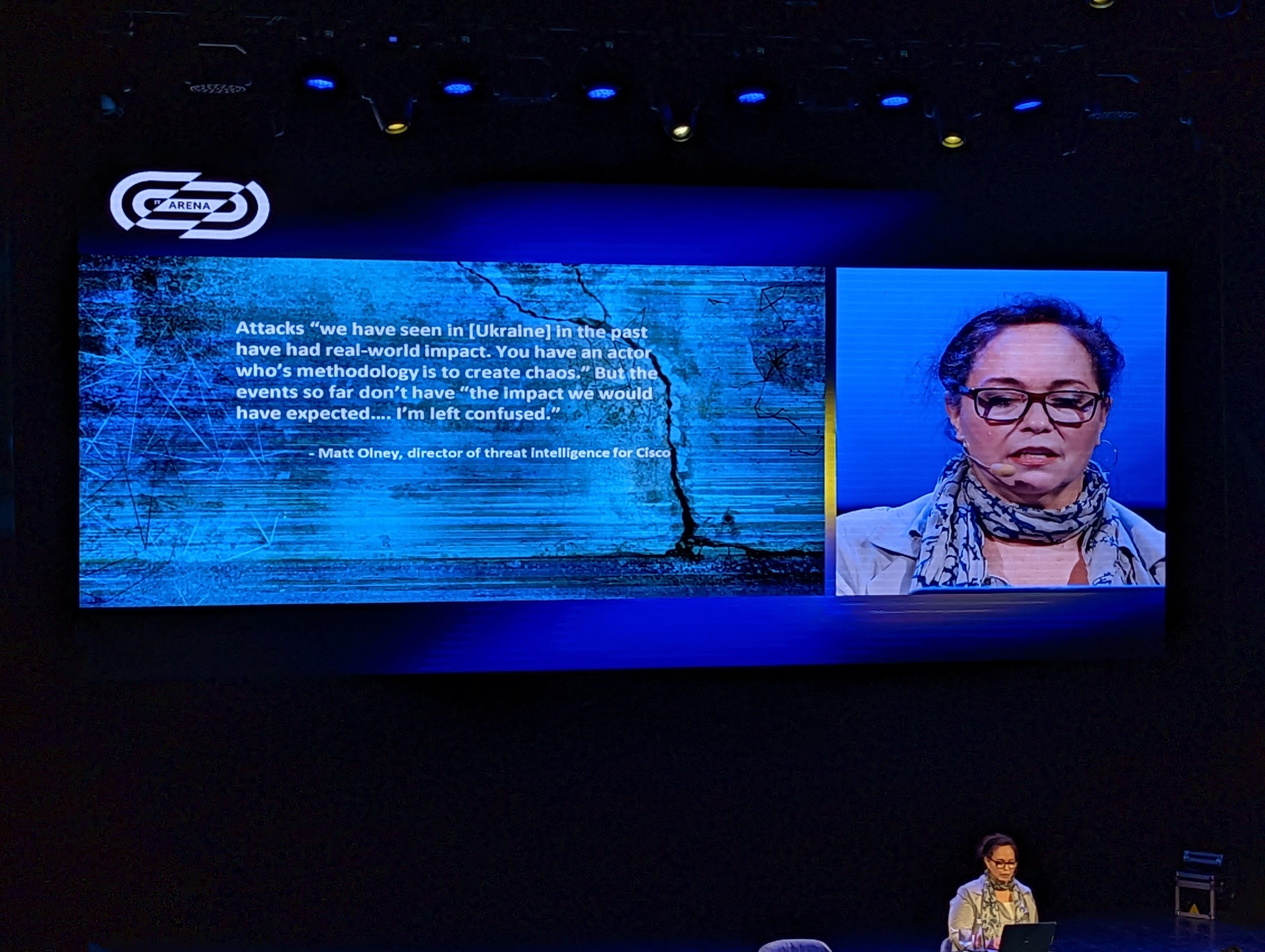

Alongside the changing physical war, there is also the largely unseen cyberwar. Many anticipated Russia would launch a massive, complex, and ingenious series of cyber attacks that would cripple Ukraine and its key resources. But it never seemed to eventuate. Or did it? As with anything involving security, it’s hard to tell and know for sure.

Journalist Kim Setter led a fascinating panel digging into a timeline of recent cyber attacks against Ukraine from stuxnet onwards and what the situation now might be.

The panel and the public facts largely agree that so far, Russian efforts have been minor. The devil (and the discussion) is naturally in the details. Have Ukraine's efforts to thwart major attacks been so successful that the public haven’t seen or, crucially, been made aware of them? Is the current strategy of Russia to just create noise and distract people and authorities from what they’re really up to for something far worse that is yet to come or yet to be discovered? In some ways, this strategy was already successful, as earlier in the conflict, local and national media was full of coverage about Russian cyberattacks, making them seem worse than they actually were.

It is an old strategy of espionage-style warfare to never fully reveal what you might know about an enemy, as then they know that you know, and you’ve lost your advantage.

The “IT army” was another subject of conversation, an “army” I even considered joining at some point until I realized i’d probably need to be able to speak Russian. It’s a ragtag, loosely organized group of individuals who organize via Telegram to target Russian businesses and data sources. Viktor Zhora, who works for the Ukrainian state responsible for the protection of information and communication protection, subtly dodged questions about them. Neither condoning nor condemning their behavior. He also slyly mentioned that he might know people who were a member but couldn’t possibly comment. He mentioned that their activities weren’t always that effective and were primarily responsible for information leaks, which others may or may not leverage for their own activities. More official bodies can benefit from the actions of less official ones without officially having an opinion on them. He likened the IT army to those all around the world who signed up to fight in the Spanish Civil war. Many at the time felt it was the right thing to do, and while the governments couldn’t take an official stance on their citizens taking part, they often didn’t do anything to stop them, and it could be said that governments benefited from their actions.

Technology as a weapon

One of the strangest feelings for me, and the other international attendees, was the widespread discussion of weaponry.

From a technical perspective, this was largely in the form of Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) or more commonly known as “drones”. Despite conversations around supply chain issues, battery concerns, user interfaces, and communication protocols, at the back of my mind was the constant thought that we’re talking about technology designed to kill and destroy.

At the time, and still, now, I am unsure how I feel about this. In this particular conflict, I support Ukraine. But until you’re in the midst of the country and the people actively involved in a conflict, that abstract distance you had before doesn’t always make you realize the cold reality of what war means. Can you support a side in a war without supporting their use of advanced weaponry? I am fundamentally a pacifist, but hearing these conversations and experiencing these thoughts caused me to question and have to reconsider a great deal of my ethical viewpoints, and I am still processing them as I write these words.

Leaving these deep thoughts aside for now…

Ukraine has jumped ahead as a developer and user of UAVs, with some projects and companies modifying relatively low-end drones for military usage. This has sparked controversy, not least from the manufacturers of these drones, but does mean that the users don’t have to worry so much about losing an eye-waveringly expensive piece of hardware in limited numbers.

Supply chain issues have hit military drone manufacturers as much as other devices reliant on microchips. But most other devices aren’t deployed in dangerous war zones with a higher likelihood of needing replacement.

The advantages of retrofitting consumer devices continue in similar ways. One of the common tactics deployed against UAVs is “signal jamming”, meaning the operator can no longer control the device. But an enemy is more likely to deploy an expensive jamming device against an equally expensive specialized UAV rather than waste it against smaller devices.

Ukraine wants to build a form of Israel’s “iron drone dome” to protect it from missiles and is finding ways and allies to help it. Meanwhile, one of the more useful and ingenious uses of UAVs in the conflict has been for detecting land mines, typically a dangerously slow operation. A local seventeen-year-old even created one using off-the-shelf components and open-source software.

Many expected future conflicts to be fought by remote operators at terminals. I just finished reading Armada by Ernest Cline. It was a ridiculous book of high-tech futuristic UAV warfare, and it seemed a flawed approach even in that book. We’re not quite there yet, and there are many opinions for and against that as a desirable future anyway. But even at this point on the potential path, the biggest problem is a common one—a skills shortage. UAV operators are a specialized breed, with skills not typically associated with other military recruits. Experts are flocking to Ukraine to train operators, potentially leaving Ukraine as a leader in another key future industry.

Final thoughts

In amongst the deep discussions, it felt strange to still hear typical startup competition pitches. I did hear a quote from someone that sums up life right now for many in Ukraine well.

You’re thinking about nuclear war at the same time as thinking about sending your kids to school.

A niggling thought at the back of my mind was, “where are all the women on stage?”. The composition of attendees was fairly even, and I wondered if, with more men serving, this would mean that women were more active in the IT sector. As many women fled overseas with their children, we have already heard a lot of their inspiring stories before arriving. On the bus from Krakow, we had one female entrepreneur who, since February, had moved to the USA, gained funding for her startup, and travelled extensively. All with her children in tow. She was just one story of many amazing multitasking women in the Ukrainian tech scene we heard from attendees.

The program for IT arena 2022 was hastily assembled no more than a month before the event. But for an event that in many ways was so different, so inspiring, and so needed, it was a shame that there wasn’t more space on stage for those sadly typically missing stories.

The slogan for the event was “Ukraine 3.0: Brave. Resilient. Digital.” and from what I saw and learned at IT Arena, I can believe it will be.

This article is part of Tech.eu's highlighting of remarkable Ukrainian startups on the one-year anniversary of the Russo-Ukrainian War. Read more ...

Would you like to write the first comment?

Login to post comments