Today sees the release of the Linux Foundation’s World of Open Source Europe Report 2025.

The report spotlights emerging trends and priorities in the European open source software (OSS) ecosystem, drawing on a quantitative survey and 14 qualitative interviews with experts from private companies, government agencies, and non-profit organisations.

The study surveyed 316 European participants from a broad mix of organisations, ranging from micro-enterprises (<10 employees) to large corporations (>20,000).

Respondents came from IT providers (39 per cent), industry-specific end users (42 per cent), and academic, non-profit, or government bodies (19 per cent). Most held IT-related roles (66 per cent), with cross-industry IT vendors making up the largest group (29 per cent).

The findings reveal an ecosystem in transition, where OSS adoption is widespread yet organisational open source maturity varies significantly, and where shifting geopolitical realities have elevated OSS from a technical consideration to a strategic imperative for digital sovereignty and strategic autonomy.

I spoke to Gabriele Columbro, General Manager of Linux Foundation Europe, to discuss some of the themes and findings of the report, as well as the broader ecosystem and the opportunity for European open source innovation.

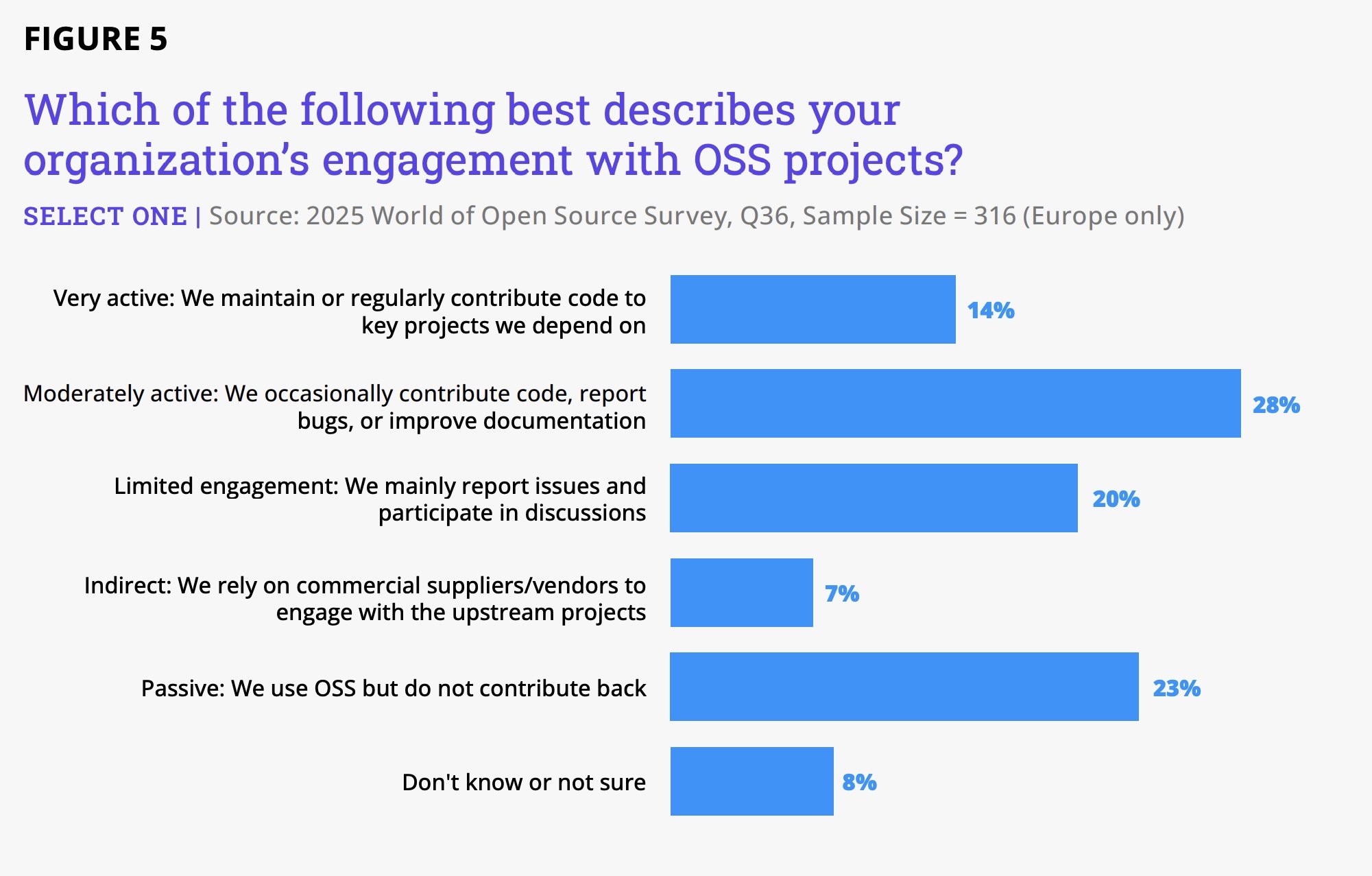

European organisations exhibit a spectrum of open source maturity levels

While European organisations show a growing awareness of the benefits of OSS, in practice they exhibit a spectrum of open source maturity levels.

14 per cent are very active and 28 per cent are moderately active in contributing to the OSS projects they depend on, while 30 per cent of organisations are passive consumers who use OSS but do not contribute back or rely on third-parties.

Research last month highlighted that the chronic under-investment in open source technologies creates systemic risks, exposing Europe to (amongst other things) cybersecurity threats, supply chain vulnerabilities, and strategic dependencies on non-European technology providers.

Too many critical projects are maintained by one or two people, often unpaid. We’ve seen efforts like Germany’s Sovereign Tech Agency or our Alpha-Omega project under the OpenSSF to spread the burden. Now, experts are calling for an EU-level sovereign tech fund — something the Linux Foundation has supported.

According to Columbro:

“Consolidation is key. Fragmented efforts need to be pulled together because ultimately we’re all sustaining the same critical infrastructure.”

Canonical offers a way forward. It launched a “giving back” fund in April 2025, which is committed to donating $120,000 over 12 months to smaller OSS projects that they depend on using thanks.dev.

Europe loves open source in principle — but the money still flows to the US

Companies invest in OSS through various mechanisms, including employing OSS contributors and maintainers, FOSS Funds, and sponsoring foundations, among others. However, despite the critical importance of OSS to companies, commercial investments in OSS remain limited. Columbro is based in San Francisco, where he contends the commercial open source model is well understood in the US:

"Companies with this model get superior exit valuations — about 7x at IPO, 14x in M&A.

Around 12 per cent of commercial open source companies reach IPO, which is higher than their proprietary counterparts. That’s why 65 per cent of VC-backed investment in open source still happens in the US, not in Europe.”

Columbro sees a number of reasons for this. First, history: the US has a tradition of risk-taking and 20 years of proven returns on commercial open source. Second, the policy and fiscal climate: most exits still happen in the US, so European founders often move their companies there. And third, there’s a cultural gap:

“Europe loves open source in principle, but executives don’t always see its strategic value.”

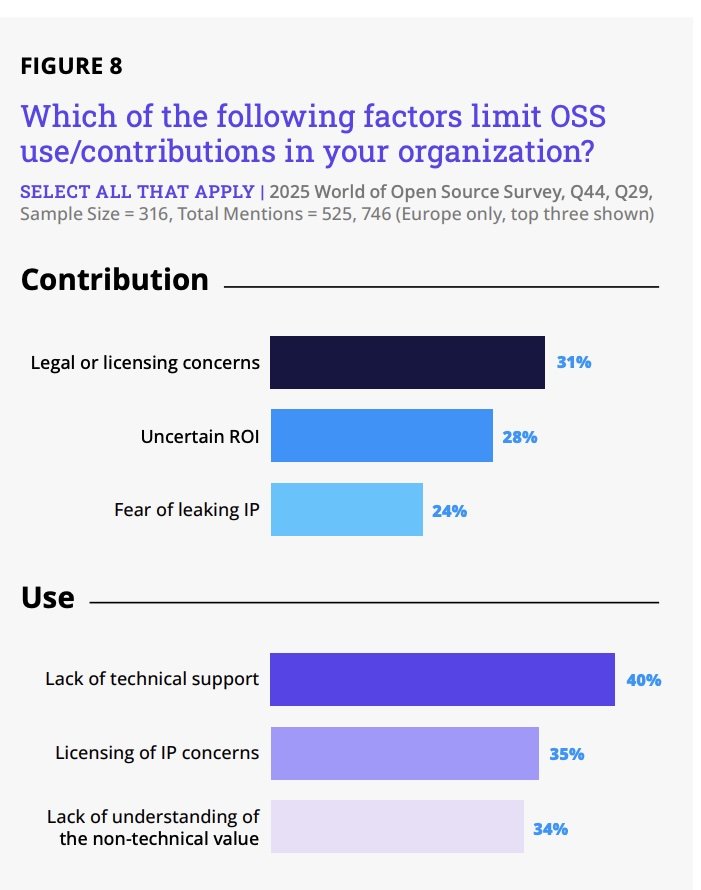

Key barriers to OSS adoption and contribution

The report shows that 86 per cent of employees love and contribute to open source, but only around 60 per cent of executives recognise it strategically. That’s a big organisational gap.

So what contributes to this lack of adoption and contribution? According to the Linux Foundations research, its combination of economic, legal, and technical barriers.

The key barriers for OSS adoption are the lack of technical support (40 per cent), licensing and intellectual property concerns (35 per cent), and a lack of understanding of the non-technical value of OSS (34 per cent).

Meanwhile, the key barriers for contributions to OSS projects are legal and licensing concerns (31 per cent), uncertainty about the return on investment (ROI) of contributing to OSS projects (28 per cent), and the fear of leaking proprietary intellectual property (24 per cent).

According to Columbro, building credible commercial endeavours on top of open source is essential if Europe wants to be a strong player in the digital autonomy conversation.

“There’s progress — continuous investment and encouraging trends — but also real gaps. Executives don’t always fully grasp the strategic value of open source, and investment levels are still lacking.”

Top-down championing of OSS by senior decision-makers, particularly in the C-suite, and the implementation of a formal OSS strategy are key enablers of organisational OSS adoption and contributions.

Significantly, 76 per cent of respondents say that engaging in OSS projects better positions their organisation to attract technical talent. Researchers contend that organisations that publicly embrace OSS find themselves better positioned to attract top-tier technical talent, as well as attract and retain talent in organisations in non IT-native sectors. Talented developers gravitate towards open source-friendly organisations, enhancing these companies’ technical capabilities and open source maturity.

A handful of sectors and industries are leading the way

Companies in a number of trailblazer industries — including telecommunications, energy, and financial services — have embraced OSS as a strategic advantage, where they not only contribute to OSS projects that they depend on but proactively collaborate together on the development of OSS, open standards, open data, and increasingly also on open AI models.

Europe doesn’t yet have an OpenAI-scale champion

Europe’s open source startup ecosystem demonstrates remarkable vitality, particularly in the AI sector. Paris has emerged as an open source startup hub, with startups like Mistral AI, Probabl, and Plakar exemplifying the talent and entrepreneurial spirit of France and more broadly Europe’s open source community.

However, the European innovation finance ecosystem presents substantial barriers to the scaling up of open source startups.

Columbro contends that the AI race is moving so fast that Europe might be better served leapfrogging. Foundational models may well become commoditised. Even OpenAI, after Sam Altman said he might be on the “wrong side” of open source six months ago — has released some open models. The real question is: where in the value chain is the real value?

“Digital sovereignty doesn’t mean “not built here.” It means “not marketed and commercialised here.” That’s the bigger issue — Europe buys American, not European, even when open source is available.

So the opportunity is in building higher-level tools and services tailored to European needs: multilingual capabilities, cultural differences, regulatory requirements. That’s where Europe can truly differentiate.”

Can we stop European open source startups from being absorbed into the US?

Columbro asserts that we need to catalyse a broader championing of open source — but not in a self-serving way, and not by splitting it into “European open source” versus “American open source” or “Chinese open source.”

“Open source is one of the few truly global ways to collaborate left, even as policy debates heat up.”

Second, consolidation. Europe has an amazing SMB ecosystem, but to credibly compete with global giants, we need fewer fragmented efforts and more scale.

According to Columbro, if you’re a large enterprise buyer, it’s easier to purchase from a big American vendor than manage a supply chain of dozens of smaller European players.

Third, investment. Some European VCs are investing in open source, but it’s nowhere near as sustained or consolidated as it needs to be.

Finally, there’s policy. Fiscal and regulatory frameworks matter and if founders don’t see a clear, attractive path to exit in Europe, they’ll continue moving abroad.

“Europe doesn’t need to rebuild everything, but it does need to consolidate technologies and pool investments so startups can credibly compete. And of course, fiscal policies must give founders a reason to scale here rather than relocate-"

Fragmenting open source by region risks weakening Europe’s strategic advantage

The Linux Foundation is known for community building and, in doing so, provides critical lessons for the wider European tech ecosystem.

Columbro contends that successful projects balance different constituencies.

Open source wouldn’t be where it is today without individual contributors driven by passion and technical excellence— but also without companies contributing developers, resources, and funding. Sometimes these groups have different motivations.

“Our role at the Linux Foundation is to provide governance structures that keep the playing field level and make sure both sides see value. Increasingly, governments and the public sector also need to be part of the equation, especially in the context of digital sovereignty.”

Second, scarcity drives collaboration. He recounts that when he started talking to Wall Street ten years ago about sharing intellectual property, the reaction was… less than warm. But as pressures from big tech, fintech, and crypto increased, banks realised open source was essential to their digital transformation — just like cloud and AI.

"Europe can apply the same lesson. Even if it doesn’t have a big tech scene like the US, it has global vertical industries—finance, telecom, and automotive.

These industries are cornerstones of Europe’s economy and have global reach. If they invest more heavily in open source and partner with startups and SMEs, Europe could create a much stronger ecosystem.”

And one important reminder: these industries are global

“Deutsche Bank, for example, won’t use “European open source” in Europe and “American open source” in the US. Fragmenting open source by region only creates more complexity. Keeping it global is key."

Would you like to write the first comment?

Login to post comments