The European Commission’s bid for technological sovereignty has a new target: semiconductors.

Speaking as part of the annual State of the Union address last week, Commission President Von der Leyen outlined her vision for how the bloc could attain independence in the production of critical technologies, at a time in which global supply chains have come under strain. One area in which the EU would like to exercise strategic autonomy is in its capacity to develop the technology, that, in Von der Leyen’s words, “makes everything work.”

“While we speak, whole production lines are already working at reduced speed - despite growing demand - because of a shortage of semi-conductors,” she told MEPs last week.

“But while global demand has exploded, Europe's share across the entire value chain, from design to manufacturing capacity has shrunk. We depend on state-of-the-art chips manufactured in Asia,” she said, adding that the European Commission would present a new ‘European Chips Act’ designed to stimulate three strands of the semiconductor ecosystem.

This includes bolstering research, increasing production capacities, and forging wider international ties, to diversify supply chains.

In a blog post penned by the EU’s Internal Market Chief Thierry Breton shortly after Von der Leyen’s speech, the Frenchman highlighted the global context of Europe’s ambitions, with the US having introduced a ‘massive investment’ framework as part of the American Chips Act, in addition to Taiwan’s bid to attain productive supremacy in semiconductors and China’s goals to ensure the long-term stability of its exports.

Breton called for the establishment of a European Semiconductor Fund, to galvanize support from the private sector for the EU’s role in this global theatre.

Much of what the Commission had to say last week was reflected in March’s ‘Digital Decade’ targets, which outline a series of long-term benchmarks, particularly in the field of semiconductor production. Here, the EU executive hopes that by 2030 it will be able to provide 20% of the world's supply of semiconductors below 5 nanometres.

This came in addition to a declaration in June from 18 EU member states to bolster manufacturing capacities by way of investment into the semiconductor industry through the EU’s recovery fund. In addition, there are plans in place to establish a new ‘Important Project of Common European Interest’ (IPCEI) on micro-technologies, focussing specifically on processors. The undertaking pledges to bring together public and private actors for research and innovation purposes.

However, there has been a laggard approach in establishing the newest IPCEI, with a recent statement from the European Semiconductor Industry Association lamenting over the delay in launching the project. “Europe cannot delay its most promising instruments in ‘turning the tide’ for the European semiconductor industry; even considerable investments into strategic sectors may lose out on the faster moving international competition,” the statement read.

The critical issue: Raw materials

At the crux of Europe’s ambitions to boost semiconductor production, rests the capacity to secure supplies of the critical materials used in the chips themselves. For semiconductors, silicon has long reigned supreme as the mineral of choice, it being in ready and ample global supply.

However, over recent years there has been a gradual transition to gallium elements in semiconductors, due to the range of benefits of combining gallium and nitrogen in semiconductor manufacturing, resulting in a boost in performance capabilities while reducing energy consumption and the physical space required for the operation of the chip itself.

In this respect, for Europe, gallium becomes a politically important mineral, in an age where green policies are at the forefront of policymakers’ minds.

And the EU Commission does recognize the criticality of gaining access to gallium minerals to deliver on broader digital and green objectives. In a communication last year, the institution listed gallium, along with 29 other resources, as a critical raw material. Further, the executive found that China far outstrips other global producers, controlling 80% of the market.

In this regard, the EU’s semiconductor goals align with the bloc’s geopolitical orientations and its alignment with the US, representing an anti-Chinese front. In this vein, a new EU-US Trade and Technology Council planned to take place next week (29 September), pitches greater alignment on global supply chains for semiconductors, as a leaked draft statement published by EURACTIV reveals.

The Commission President’s State of the Union speech laid out some ambitious proposals for a technology that has become a staple in modern devices. There is little doubt that Europe’s capacity to compete on the global stage in the development of next-generation technologies is hindered by a lack of resourcefulness and forward-thinking in terms of Europe’s productive capacities for semiconductors.

EU Internal Market Chief Thierry Breton’s proposals for developing European fabrication plants that can produce in high volumes advanced semiconductors is an ambitious objective in the long-term. But should the EU not be able to independently source some of the critical materials required in the fabrication of the semiconductors of tomorrow, such goals will rely on tactful diplomacy with global partners – relations at the mercy of wider geopolitical forces, which could ultimately compromise the bloc’s objective for attaining a genuine technological sovereignty.

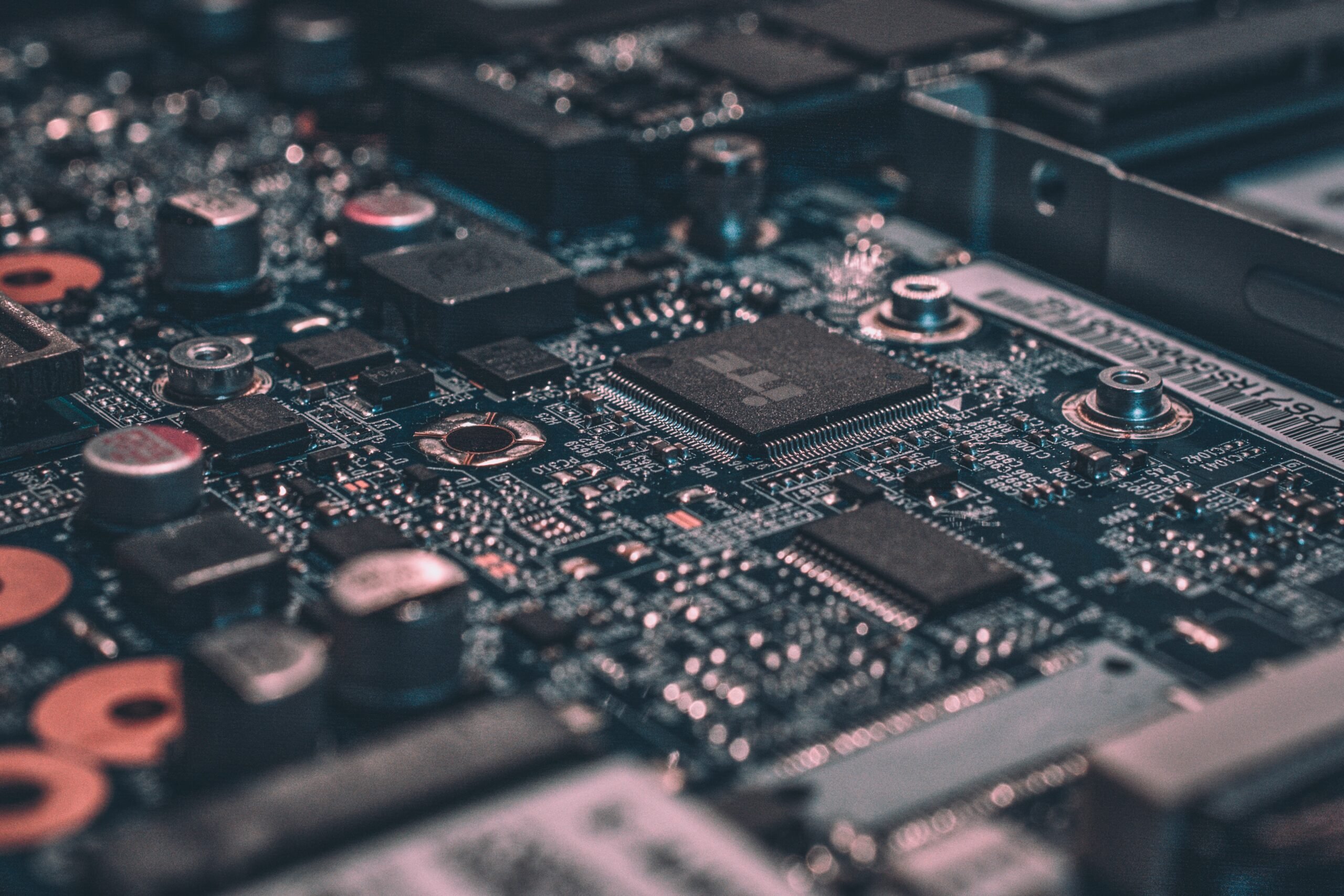

Featured image credit: Alexandre Debiève / Unsplash

Would you like to write the first comment?

Login to post comments