Electronic voting has been a hotly debated topic in several European countries with some more open to the idea than others. Despite the discussion, online voting in parliamentary and local elections doesn't seem to be catching on.

We've put a great deal of faith in online banking and e-commerce, but that level of trust doesn't show signs of translating into the world of voting.

“The theft of online bank credentials or other forms of commercial identity theft can have a serious negative impact on a specific victim affected,” said David Emm, a Senior Security Researcher at Kaspersky Lab. “But they don’t threaten to undermine online commerce itself, whereas even selective hijacking of voters’ online credentials could have far-reaching consequences, which include undermining a country’s political system.”

E-stonia

Estonia is the only country to run Internet voting on a wide scale in accordance with its generally successful eGovernance practices, where citizens can access services through their eID card.

However, lately, its online voting mechanisms have come under scrutiny. Meanwhile, Norway has put an end to its online voting trials due to a number of concerns, such as votes being altered.

SafelyLocked co-founder and EFF Pioneer Award winner Harri Hursti said that paper ballots are simply more effective and reduce risks as compared to Internet voting, which faces the problem of not being able to have a secret ballot that’s auditable at the same time.

“We don’t know how to do that,” Hursti tells tech.eu. “We do not have fundamental mathematical knowledge on how to do this.”

Joseph Kiniry, a Principal Investigator at US R&D firm for government clients Galois, has previously lectured at a number of European universities and is currently involved in a research project investigating the design of online voting.

Kiniry has been critical of Estonia’s Internet voting, saying there has been little transparency in the system. He argues that, if a well-meaning hacker activist even tried to attack the system to prove its flaws, they would face serious legal consequences.

Additionally, he conducted an audit of the code within 48 hours of the release and found “numerous problems” with it, which he presented at a VoteID conference in the UK last year.

Estonia’s e-voting faces criticism

When election day rolls around in Estonia, many citizens do not need to leave their home. They merely login to their public services platform using their electronic signature and ID card and cast their ballot.

Estonia is the only country to do so on a national basis. According to the government, between 20% and 25% of voters use this online system in parliamentary and municipal elections, but the rest of Europe remains largely unconvinced.

Following Kiniry’s audit of the code, Hursti and a team of independent researchers from the University of Michigan and Open Rights Group conducted an investigation into the security infrastructure behind Estonia’s Internet voting system, which they deemed unsafe and advised on its immediate withdrawal.

When researchers observed staff setting up the voting system in Tallinn leading up to the election, they noted a “lax operational security”, where software was downloaded over unsecured HTTP connections. They also recorded incidents of staff entering passwords and PINs in plain view of a camera and even WiFi passwords stuck up on office walls.

The researchers then moved on to replicate the Estonian system in their lab and put it through some rigorous security tests only to find the system is fatally flawed. “We have confirmed these attacks in our lab — they are real threats,” the researchers said. “We urgently recommend that Estonia discontinue use of the system.”

According to the research team from the University of Michigan, the security architecture is precariously outdated, failing to evolve and adapt with the times since its introduction nearly ten years ago. Additionally, with state-level cyber-attacks much more prevalent now, the system simply isn’t up to task.

Most importantly, voting outcomes could be altered. With their replicated system, the researchers were able to launch their own attacks – this included server-side attacks, which could decrypt votes and alter the final count as well as client-side attacks that could easily bypass officials’ security practices. Also, malware that infects a regular voter’s computer could steal votes and switch their choice to a different candidate.

“What we found is that, if you’re going to build a system like this, then we believe it needs to be of the utmost quality because if something goes wrong, it’s going to go seriously wrong,” said Kiniry when acknowledging the system's messy code with no documentation or descriptions.

“Based on the system’s design and implementation, there was no guarantee that the vote actually got into the ballot box,” he added.

“There was also no guarantee in the system that a vote coming in was from a legal voter. Any vote that was received would simply be stuck in the ballot box. It’s quite remarkable. It’s one of those properties you would think is fundamental but, in fact, it wasn’t.”

Even more, voters had no assurance that the election was actually a true representation of their intent since there was no proof that votes were cast, recorded and tallied.

“The way the system was built, any number of people running the system could have changed the outcome of the election, it had poor policies, procedures and technologies to ensure a legitimate election,” said Kiniry.

Update: we've received the following statement from Priit Vinkel, Head of Elections Department, Chancellery of the Riigikogu (Estonia's parliament):

We are concerned of the one-sided and polemic arguments brought in this article.

Please find the Estonian statement on the accusations made by Mr. Kitcat and others (originally on the article covered in the Guardian) here. Also, please find a detailed analysis of the accusations, written by Mr. Anto Veldre of CERT-EE, here.

A unique set of problems and challenges

The fundamental issue comes down to auditing votes and maintaining a secret ballot, which is not currently possible.

“Voting has a very unique set of problems and challenges,” said Hursti, “You have to have voter secrecy, the vote has to be a fixed ballot and, at the same time, it has to be auditable. The third problem comes from the stakeholders – whether they are voters, poll workers, a candidate – everybody has to be able to verify the result.”

Hursti doesn’t expect that online voting will be tenable in the next ten years, but perhaps in his lifetime.

“We can figure out the mathematical algorithm, but then comes the next problem,” he explained, “If you look today, the people who understand the research done in algorithmic encryption, there's about 500 people in the whole world who understand how the mathematics works. So if this kind of system is invented in 10 years or 20 years from now, who’s going to audit?”

This raises the question of trust in a complex manner – how do we know the system works and how do we prove it? Should these problems be solved, it will not only benefit voting but could eventually be applied in many other areas as well.

For now, Hursi is clear on one thing: calling for the withdrawal of Internet voting.

“We don’t have any idea today how to make electronic voting over the Internet work,” he said. “We don’t know for certain if it’s possible, but I suspect sometime in the future – not in the next ten years, but maybe in my lifetime – it will be possible.”

What will Estonia do now?

Since the conclusion and publishing of the investigation, researchers have had little contact with Estonian officials, who seem intent on continuing with Internet voting.

“We have had some contact with the Estonian Elections Committee and the Electronic Voting Committee,” explains Jason Kitcat of the Open Rights Group. “It seems clear from those meetings and subsequent public statements by the Estonian President and Prime Minister that they are politically committed to pursuing the i-voting system as a symbol of Estonia’s electronic government programme.”

However, is there anything Estonia can do in the interim to address some of these issues?

“Nothing, other than switching it off,” says Kitcat. “The vulnerabilities and risks we identified are many and are complex. Within the limitations of current technology they simply cannot be adequately addressed.”

Joseph Kiniry has had some contact with Estonian officials too. “Basically what has happened in the meantime, much to our amusement is that the company that built the Estonian system, which is sort of a spinout consultancy of the government, has now either merged with or done a business deal with a major supervised voting company called Smartmatic,” he says.

Smartmatic, headquartered in London, is one of the world’s largest vendors for electronic voting technology.

“They have formed a centre for excellence in Internet voting or something like that in Estonia,” explains Joseph. “So it looks in essence, Smartmatic has done a deal with them to give Smartmatic, or a combination of the two, an Internet voting product for the world.

“Estonia is carrying on but more so they’re now trying to export their technology to the rest of the world via one of the main vendors. That’s a fairly serious non-response. To get this level of criticism and then take it to the next level and try and sell it to others requires quite big cojones.”

Norway calls a halt to online voting

Even with these problems and concerns, it has not stopped other countries from at least trying out Internet voting through various means.

In late June, the Norwegian government decided to end its trials for online voting which it had conducted in 2011 and 2013 elections due to a number of concerns relating to security, privacy, and double voting.

Minister for Local Government and Modernization Jan Tore Sanner said that while the government was interested in pursuing Internet voting, the trials didn’t appear to instil too much confidence in voters.

Turnout did not increase significantly either. In the 2013 trial, the BBC reports that only 38% of those eligible to vote online chose to do so. The average voter turnout for parliamentary elections in the past has been around 77%. Meanwhile, another of the chief concerns from the tests was that votes would become public.

Norway’s Institute of Social Research determined that voters had limited knowledge of the system’s security mechanisms, which affects the idea of a free and fair vote.

“This shows how important it is that elections are conducted at polling stations where election officials make sure that the principle of free and fair elections and the secrecy of the vote is respected,” said Minister Sanner.

In some cases, it would be possible for a voter to cast their ballot in the morning and then travel to a polling station to cast a paper vote. The risk of double voting is a dangerous set of circumstance for any voting system. To prevent it, officials would require another mechanism to invalidate someone’s paper vote if they opted for online voting, which needs to be implemented before polling day.

Internet voting in Norway is on the backburner for now but what sorts of similarities can one note between the Estonian and Norwegian efforts?

Scytl: a viable alternative?

During Norway’s trial, officials worked with Spain’s Scytl, an e-election company that grew out of a cryptography research group at the University of Barcelona. While many of the concerns are the same for security and privacy, Scytl’s product is better than that of Estonia’s Cybernetica, says Joseph Kiniry.

“Based upon what we’ve seen of their technology, because they are a primary component in the Norwegian system and several others, their engineering is significantly better than Estonia,” he says. “That being said, they don’t build a verifiable Internet system and therefore voters can’t check that their votes have been properly recorded or cast or tallied. They seem to be on a path to doing so.”

Verifiability is the one key trait that determines if an online system can be successful. Voters need to have the confidence that their vote has been cast and it has been tallied. “When you move to a digital realm, then you have to use sophisticated measures to attempt to do that and while there’s a lot of research on how that could be done, no one has actually done it properly,” says Joseph.

“I have a copy of their code for example because they made it public as part of the Norwegian experiment and I have audited that code as well,” he adds, “and I found numerous issues and I sent those issues to them and I made a number of recommendations."

“I advocate, both when I was a professor and now as a professional, that it shouldn’t be used for national elections until such time that they make it a verifiable product.”

National and large city elections remain a dangerous test bed for Internet voting with too much at stake. However, local elections on a small scale may provide more opportunities for testing once a verifiable product has been established.

“I think they have good intentions, they’ve tried to do something quite dramatically better than the rest of the world with regards to engineering and transparency but they made some fundamental assumptions early that have hurt them in the eye of the research community,” says Joseph.

“Scytl was a sub-contractor for them so Scytl was responsible for the cryptographic core of the system and the Norwegians sort of built everything around that and what they built in the end, in our eyes, is something that’s too large and too complicated for what it does.”

Could Internet voting activate young voters?

One of the main motivations for pursuing Internet voting is convenience as it may get more people to vote, especially young people.

“But if you look at the Estonian official statement, the younger voters are dropping in Internet voting,” explains Harri. “The same in Norway, the young voters were not activated by Internet voting and there is a very obvious reason for that.”

This reason appears to be an immersion in Internet culture, he says. “The younger generation have been growing; the Internet has always been a part of their lives,” explains Harri.

“Their email address has been hacked a couple of times by their school friends, their Facebook account has been hacked a couple of times and on their multiplayer game online they’ve been playing, their stuff has been stolen a few times.”

Once you are familiar with cyber threats on a first hand basis, it’s hard to turn a blind eye to it elsewhere.

What’s next for online voting?

Companies like Scytl continue to pursue online voting and is active in many countries outside of Europe too. Scytl is currently expanding its service in North America and has recently appointed a new General Manager for the US and Canada, Brian O’Connor, and is clearly eyeing up further expansion.

Research in the US will have major implications for Internet voting practices in Europe and beyond. Joseph Kiniry is leading a 25-person team of the best minds in the field, conducting research on how we can design Internet voting as a real, verifiable procedure.

The End-to-End Verifiable Internet Voting Project (E2E VIV Project) is run by the non-profit Overseas Vote Foundation, aiming to find a voting solution for overseas military personnel and people with disabilities.

Kiniry is the lead technical manager of the team that consists of cryptographers from Microsoft; University of Iowa scientist and author of Broken Ballots: Will Your Vote Count?, Dr. Douglas W. Jones; and Dr. David Wagner of the EECS Computer Science Division at the University of California Berkeley; and a host of other esteemed experts.

The project commenced in December of last year and has 18 months to find a path to design an end-to-end verifiable system, which could have substantial repercussions on voting in the digital age.

“I’m in the middle of the whole thing, fostering communication and trying to get these people that actually don’t agree to find common ground and see if we can come up with something,” Joseph tells us. “Right now I don’t know the answer.”

A wide consensus on the tenability of online voting may not be right around the corner but there are certainly a lot of interested parties working on it behind the scenes. Finding a design is the first step with years of further research needed to build the system.

“The research community knows it’s possible to design a verifiable Internet voting system, technically, but whether you can do that in a way that’s usable and accessible and cost effective and deployed in a secure fashion is a hypothesis,” says Joseph.

“We don’t know the answer to that. We’re going to work hard on it for a year and we’re either going to say no at the time, that 25 people of the best in the world can’t figure it out or we’re going to say yes, under these specific constraints.”

Harri Hursti sums up the scenario quite well: “Right now there is a huge amount of academic prestige available for the person that solves this problem.”

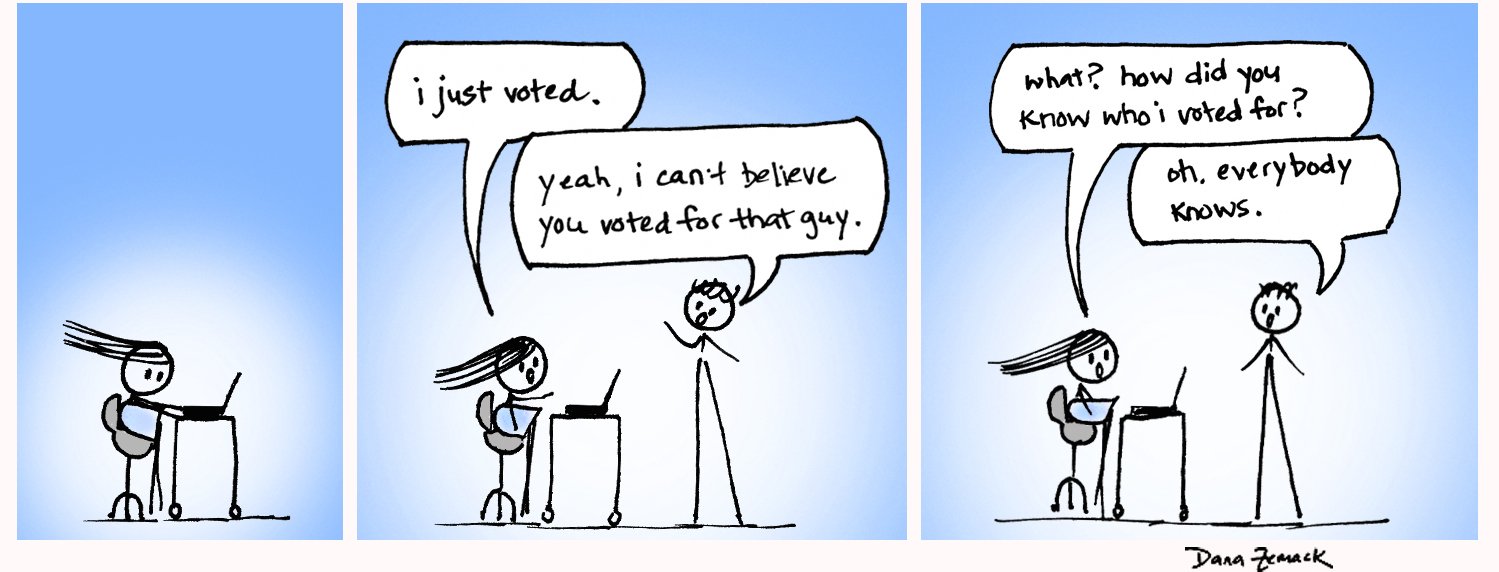

(Featured image credit:) Illustration by Dana Zemack – follow her on Twitter.