Pets have firmly pawed their way into our families. In Germany alone, 34.4 million households own at least one pet, with cats at the top of the tree with 15.2 million fluffy felines in 24% of homes — a further 10.6 million own dogs.

Over the last few years, we've seen an explosion in pet tech startups delivering services like pet food, remote health care, and insurance.

But one of the most exciting trends is connected hardware, offering ways to engage and monitor our pets, helping improve their quality of life.

However, building connected hardware is challenging, with the costs of materials, multiple testing cycles, user engagement, and staff recruitment and retention. Despite this, all over Europe, pet tech startups are using hardware to make a difference.

Mental stimulation for dogs

Go Dogo was the brainchild of CEO and cofounder Hanne Jarmer in 2016, who needed a way to stimulate her dogs. A department head at the Technical University of Denmark, she was struggling to keep her dogs entertained while at work.

She shared:

"I'd give them a puzzle toy, then they would chew it, and it would get stuck in their throat. I was hiding treats in my living room, and they found them before I left."

Research revealed that games are often too easy or difficult, so the dog solves them too fast or simply gives up. There is only a limited possibility for progression and no instruction or feedback.

Jarmer had the idea of doing some visuals involving TV and computer vision. The closest thing she could find was pet cameras without a learning or mental stimulating interaction -- you had to add it yourself.

She bought a treat dispenser and made some films "with me, just saying some of the commands my dogs already knew. And I just tried to see if it was possible. So I simulated the product without building it. And they liked it. They quickly learned they had to move to get the treats."

But how do you design a product that puts the animal's welfare first, much less one that human owners will buy?

Pet tech testing and animal-centred design

Earlier this year, I spoke to Sarah Webber, a lecturer in human-computer interaction seeking to design better tech for animals (including humans).

She conducts research as part of the Human-Computer Interaction group at The University of Melbourne in partnership with Zoos Victoria. One of her projects is designing games and apps for orangutans at Melbourne Zoo.

Key to Webber's work is the idea of participatory design, which involves allowing the end user to provide input and feedback for prototypes. She explains,

"We want to design genuinely useful devices for animals. So currently, we're interested in how tech fits into the zookeeper's normal practices of care and husbandry and monitoring well-being and how we can adapt it to do that better."

Webber and her cross-disciplinary team are currently interested in the long-term use patterns of how orangutans engage with tech. This means how the technologies are adapted, adopted, and appropriated.

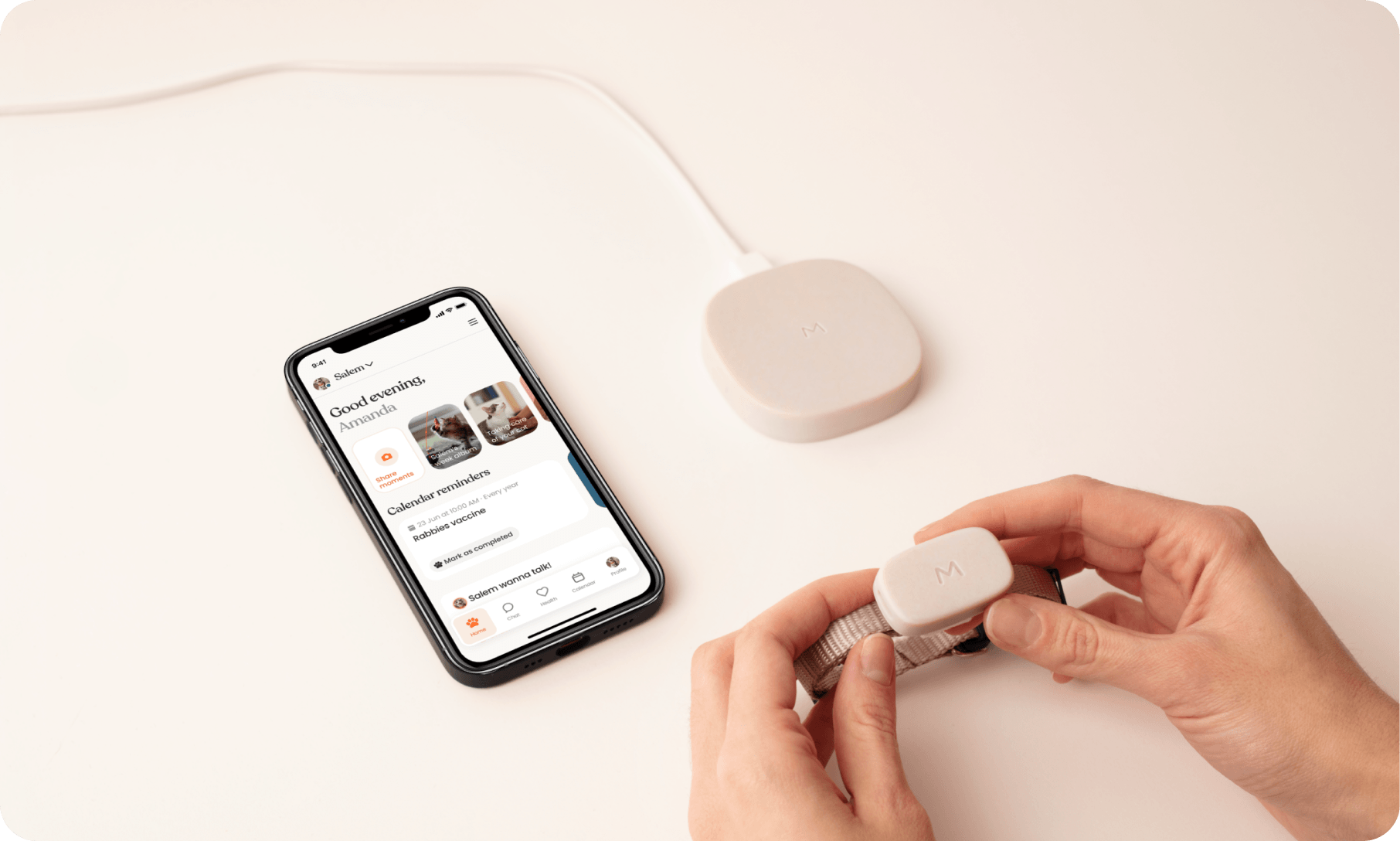

Ali Ganjavian is focused on improving the lives of another species much closer to home — cats. He's the CEO of Moggie, a wearable pet-tech company on a mission to make cats live better and longer. When it comes to pet startups, cats are far less represented despite being the most popular pets.

He agrees that putting the user at the centre of decisions is crucial, noting,

"Coming up with a super lightweight device that doesn't hurt cats' necks was one of our top priorities."

Moggie opted to design a lighter wearable device even though it needs monthly charging instead of the longer life awarded by a larger battery.

Webber asserts that pet tech that takes the pet out of the design process is most likely problematic at best and damaging.

An egregious example is the use of remote lasers to play with your dog at a distance:

“This is a big no-no from the pet training and animal behaviourist world. Don't use lasers to play with your dog or your cat; it's not good for them, there is a chance that they might develop obsessive-compulsive disorders.

Don't integrate them into pet technology, please."

Go Dogo offers a valuable insight into how pet-centred design can work in practice. It started its initial tests with rudimentary devices at a doggy daycare. Tests at home using an inexpensive prototype turned testers into prospective customers.

Today Go Dogo uses the home TV to give the needed instructions and feedback, and it dispenses treats as rewards when the dog does an exercise correctly -- or, in some situations, to support the motivation to keep trying.

Computer vision enables Go Dogo to recognise the dog's movements, and the intelligent software adapts to each dog individually. It gradually increases the level of difficulty to ensure adequate mental stimulation.

The device is available across Europe and the US.

Besides pet owners, it's proved popular with scientists because it allows dogs to interact with a device in their natural habitat at home. It's currently involved in research with the Family Dog Project in Budapest, and Hunter College's Thinking Dog Center in New York, which explores scientific questions about the psychology of dogs.

However, Jarmer notes that marketing isn't easy and can be challenging to communicate what Go Dogo is to the general public.

"They think it's training because the dog is told to sit or lie down. But that is not why we are doing it. That's just because we can teach the neural networks to recognise the movements. We're not teaching a dog to sit or lie down."

Wearable tech tracks data changes and helps detect hidden illnesses

The use of wearable tech to monitor the physical health of animals requires less explanation.

In Barcelona, DinBeat produces a series of vests that record heart rate, respiratory rate and temperature in critical care, post-operative and cardiology settings. In various sizes to suit dogs, cats, and even horses, animals can wear vests during walks with data transmitted to an app.

Wearable tech can also monitor pets at home. Ali Ganjavian came up with the idea for Moggie when their cat died, and they had no idea it was unwell. He notes, "The cat is the family member that knows everything about you, but you don't know anything about them."

While developing a prototype, the company partnered with the University of Uppsala in Sweden and found that their data can help vets more quickly uncover serious illnesses such as diabetes and osteoarthritis.

Moggie tracks and maps behavioural changes such as jumping, sleeping and playing, providing alerts if the frequency of these behaviours changes.

Importantly, it also acts as an educational tool between pet and owner, providing information about why cat jumping is essential and what it represents.

The company is currently halfway through a successful crowdfunding campaign on Kickstarter.

Webber contends that there's a need for tech that reduces the gaps in people's knowledge about what makes for a good, happy life for a dog or a cat.

She suggests, "Less jumping could suggest an injury, for example, in a young dog, or sudden activity during the day may mean that something at home is making them less rested."

Surprisingly a key challenge in pet care is that behavioural training is only a small part of veterinary training unless a student opts to do additional qualifications.

Webber shared that "traditionally, animal welfare was all about avoiding neglect or negative states, but now, research is interested in "how we ensure that animals who are in managed environments with humans are in control of their lives and their situations can have a good quality of life rather than a just not bad quality of life."

This offers a great opportunity for startups to develop pet-centred design which enriches and elevates the lives of the beloved pets who hold a special place in our hearts and homes.

Would you like to write the first comment?

Login to post comments