Car making exists in a challenging environment — marked by geopolitical tensions, high interest rates, raw material costs, CO₂ standards, increased competition in EVs, and pricing pressure.

I recently took a press trip to Shanghai, Hangzhou, and Hangzhou City, to learn about Renault Group’s (hereinafter referred to as Renault for brevity) efforts to re-release the updated Twingo, the Twingo E-Tech electric and discovered a company reinventing how it develops vehicles.

The original Renault Twingo, launched in 1992, sold more than 4.1 million units across 25 countries. But as the small-car segment shrank to under 5 per cent of the European market, even the EV version struggled, and Twingo was discontinued in 2024. It's an uncomfortable truth that SUVs dominate most cities where they don’t belong. In 2021, SUVs accounted for approximately 48 per cent of passenger car sales in China.

By 2024, SUVs represented roughly 54 per cent of all new passenger vehicle registrations across major markets in Europe. Can Renault get people out of their oversized vehicles and into the more compact Twingo E-Tech electric?

For Europe’s tech and startup ecosystem, Renault’s Twingo rollout is more than a story about one car — it’s a case study in how legacy industries must rethink speed, partnerships, and global learning if they want to stay competitive.

Inside Renault’s China playbook: faster cycles, leaner teams, cheaper cars

To design an affordable and competitive electric city car, Renault has radically transformed its R&D with the Twingo E-Tech electric, the first model in its “Leap 100” programme — named for its goal of developing a car in just 100 weeks. It’s the fastest vehicle programme in Renault’s history.

To achieve this, Renault created a new organisational model combining European expertise with Chinese innovation, built around three pillars: Ampere (its electric vehicle business), ACDC, and the Novo Mesto assembly plant. Ampere led the project across its key stages in France, China, and Slovenia.

Development began in France using the AmpR Small platform and a streamlined governance setup to speed decisions and reduce complexity.

In terms of the company’s focus on China, Renault’s CEO, Luca de Meo, told staff he wanted to do a car for less than €20,000 in under two years.

While the French team initially told him it was impossible, the Chinese said “no problem”.

In response, Renault opened its Advanced China Development Centre (ACDC) in Shanghai in January, bringing together strong local partners, resident engineers, and dedicated teams focused on strengthening the company’s overall competitiveness.

According to Renault CTO Philippe Brunet, “We are here to learn and to compete.”

That pretty much sums up Renault Group’s strategy in China right now. The company is intentionally embedding itself inside China’s NEV ecosystem — not just to observe it, but to learn from it and bring the innovation back to Europe.

This includes faster development cycles, smarter supply chains, and ultimately brings vehicles like the new Twingo to market in under 24 months –” though we’re aiming for 21 months,” said Jérémie Coiffier, Project Engineering China - ACDC.

Renault has shaved time off their development cycle by concept freeze to engineering prototype in around nine months by tightening design loops, relying more heavily on software-first design, full virtual-car models, and simplifying supplier nomination.

The follow-on phases — engineering prototype to pre-plant trial, and then to start of production — are shortened further through the use of soft-tool hardware, parallel workstreams and closer alignment between engineering and industrialisation teams.

The time savings are significant: 16 per cent shaved off upstream planning, 41 per cent off development and pre-industrialisation, and 26 per cent off the industrialisation phase itself. All of this means new models can reach customers sooner.

How Chinese suppliers are accelerating Renault’s Twingo

A key part of Renailt's acceleration comes from collaborating with 30 Chinese suppliers and engineers, many of whom already support both global and domestic OEMs.

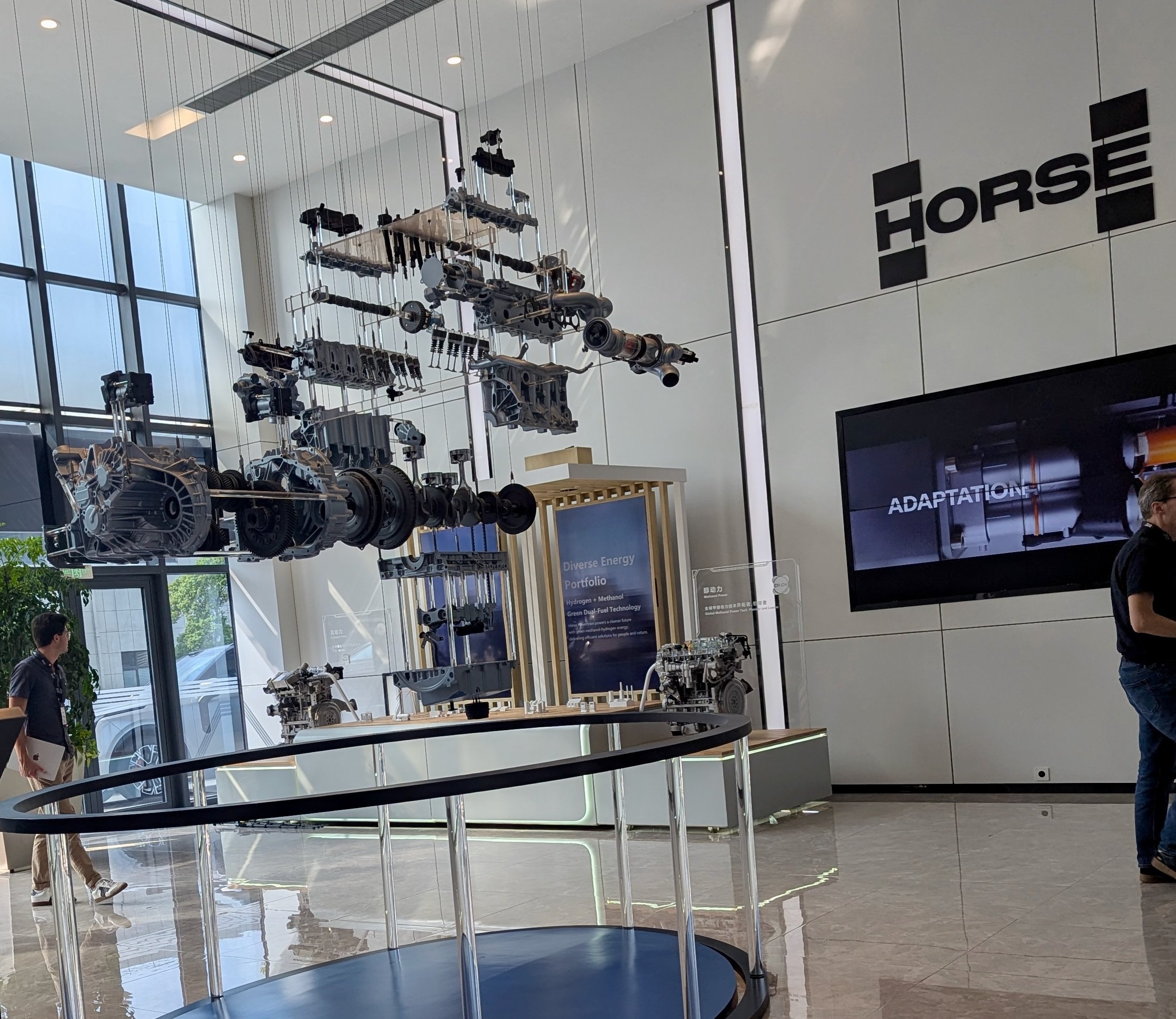

There's also HORSE Powertrain, a UK-founded but Shanghai HQ company created by Renault and Geely in 2024 to build engines and hybrid systems for cars. This matters — China uses NEVs, or New Energy Vehicles to refer to non-ICE vehicles, encompassing BEVs (Battery Electric Vehicles), PHEVs (Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles), FCEVs (hydrogen Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles), and those powered by sustainable fuel.

In response, HORSE positions itself as a major supplier for markets where full EV adoption is progressing unevenly, offering scalable, lower-emission powertrains that let carmakers outsource ICE and hybrid development while focusing their own resources on electrification. This setup helps cut part-level development costs, tooling costs, and sourcing timelines.

At the moment, about 40 per cent of Twingo components come from China and around 60 per cent from Europe and other regions (by value).

That balance is expected to shift further toward Europe once battery production is localised at Renault’s Novo Mesto plant, where the project ultimately transitions from prototype into full production.

As part of this integration, staff from the Novo Mesto plant have also been travelling to China to collaborate directly with suppliers and engineering teams.

Ultimately, Renault’s two-year development cycle now brings it much closer to the pace of its fastest global competitors.

Where European OEMs traditionally operated on four-to-five-year timelines, Renault has essentially split that in half.

It’s now within reach of the 24–30 month cycles seen at agile Chinese players like BYD, NIO, XPeng, Geely. In China’s quickest startups, facelifts and software upgrades appear in 12–18 months. Renault isn’t aiming to become a Chinese EV company — but it is clearly adopting critical parts of the playbook.

Investment in Chinese automotive ecosystem

In July, Renault's electric vehicle business Ampere signed a deal with Chinese partners, including CICC Capital PE, in Hangzhou to launch an EV industry investment fund. The fund will target innovation in areas such as batteries, autonomous driving, smart cockpits, automotive software and AI within NEVs.

The fund is focused on Chinese companies, and it's unclear what this will mean for the European startup ecosystem. This week saw reports that Renault has ended a project with French global automotive supplier Valeo to develop a new rare-earth-free electric vehicle motor, instead looking for a cheaper Chinese supplier.

Yet, according to Ampere. Even if a Chinese company does contribute to the stator, the motor would still be made in Renault's plant in Cleon, France, with silicon carbide modules provided by Franco-Italian firm STMicro for the inverter, another central EV component.

Further, Renault’s CVC arm invests in companies like Wandercraft and Verkor and is a founding member of Software République, an open innovation initiative with partners like Atos, Dassault Systèmes, Orange, STMicroelectronics, and Thales. This program launched a dedicated startup incubator in Paris to advance sustainable, secure, and intelligent mobility, driving forth companies like COMPREDICT and Entropy..

The price, policy, and infrastructure divide shaping China-Europe EV adoption

China and Europe are moving through the EV transition in completely different ways, and the contrast is hard to ignore. In China, EV adoption is highest in southern regions where climate is naturally favourable. In Europe, uptake is strongest in the colder north, driven much more by policy and incentives.

That divergence shows up in consumer expectations too. Chinese buyers tend to want digital-first cabins, smart assistants, and deep app ecosystems. Europeans are still prioritising range, charging performance, practical features — and very predictably — privacy. Further, China’s fleet market sits at roughly 10 per cent, whereas Europe’s is closer to 60 per cent and remains one of the biggest levers for EV adoption.

Pricing reinforces the split: Chinese EVs average around €19,000, versus roughly €35,000 in Europe. And on infrastructure, China is well ahead, with around 4 million public chargers compared with Europe’s ~970,000, plus a far denser DC fast-charging network. In short: two ecosystems, moving at different speeds for very different reasons.

The dark side of hyper-scaling: China’s EV sector falls into involution

However, while Renault’s relationship with the Chinese automotive ecosystem shows its capacity for speed and innovation, it’s worth taking a look underneath the hood at how the local automotive market is faring.

While China’s NEV market penetration stands at 50 per cent, news reports that the sector is “Bloated by excessive investment, distorted by government intervention, and plagued by heavy losses,

Essentially, China is undergoing a process of involution, where policy-driven overinvestment has created an oversupply of vehicles that exceeds market demand.

China’s total vehicle production capacity hit more than 55 million units last year, while actual sales were barely half that. Factories that once ran nonstop now hum at only 50 per cent capacity.

The result is a deflation of price, thinner margins, and less profitability. Factories reduce their opening hours, and jobs decline, especially as factories are staffed by robots.

According to Autopost, of the roughly 130 EV manufacturers in China, only four made money last year — BYD, Tesla China, Li Auto, and Geely.

It follows that more and more Chinese automakers will look to the European market to increase profits. For the first half of 2025, Chinese-made cars achieved a record ~5.1 per cent share of the European market. Combined, Chinese car brands outsold Mercedes in June. While Chinese EVs are subject to sizable tariffs, there are reports that launching local production in Europe and a focus on hybrids has offered a loophole against the cost.

Europe builds a unified software stack

Renault is not the only company looking to advance through software. Eleven automotive companies, backed by the German Association of the Automotive Industry (VDA), signed a Memorandum of Understanding in June this year to cooperate on open-source software development. Their goal: speed up development, improve efficiency and security, and create a shared software platform for series production — with a modular code-first approach scheduled for rollout in 2026.

The aim is to develop non-differentiating vehicle software based on an open, certifiable software stack – and thus accelerate the transformation to software-defined vehicles. This should not only reduce the development effort but also speed up the market launch.

For Renault, the Chinese ecosystem offers unmatched speed, supplier density, and technical agility — which is exactly what Renault is trying to absorb through ACDC Shanghai.

But China’s overcapacity and race-to-the-bottom pricing also underscore why Renault is not trying to replicate the Chinese market model in Europe. Instead, it’s selectively importing the methods — faster development loops, integrated suppliers, software-first design — while avoiding the structural traps that have pushed much of China’s EV sector into unprofitability.

Where to from here?

Chinese overproduction means a growing surplus of EVs is being pushed into export markets, with Europe becoming the primary destination if the trends of Australia and the Middle East are anything to go by.

This influx is already driving EV prices down, particularly in the small and mid-size segments where margins are tight and European carmakers have traditionally struggled to compete on cost. The challenge now is to ensure that European startups are not sidelined by the gravitational pull of China’s hyper-scale supply chain.

Overall, if Europe can combine startup ingenuity with industrial reinvention, it still has a critical shot at shaping the next era of global mobility rather than simply importing it.

Would you like to write the first comment?

Login to post comments