In 2025, the European Space Agency turned 50. Founded on 30 May 1975, when the ESA Convention was signed by ten Member States, it has since grown into a pan-European institution spanning 23 Member States, three Associate Members, and a widening network of international cooperation agreements.

Anniversaries are good moments for celebration — but also for taking stock.

ESA’s last five decades have been defined by scientific ambition, industrial development, and European cooperation. Its next chapter will be shaped just as much by commercial competition, geopolitics, and the very down-to-Earth reality that space is now critical infrastructure: for connectivity, navigation, climate monitoring, security, and more. To understand what this shift looks like in practice,

I spoke with founders and operators working with ESA across manufacturing, sustainability, launch, Earth observation, and space traffic management.

From components to full systems — and the leap to GEO

For Emile de Rijk, CEO of SWISSto12, ESA’s role is clearest when you look at how European companies move up the value chain: from specialist components to full, commercially viable systems.

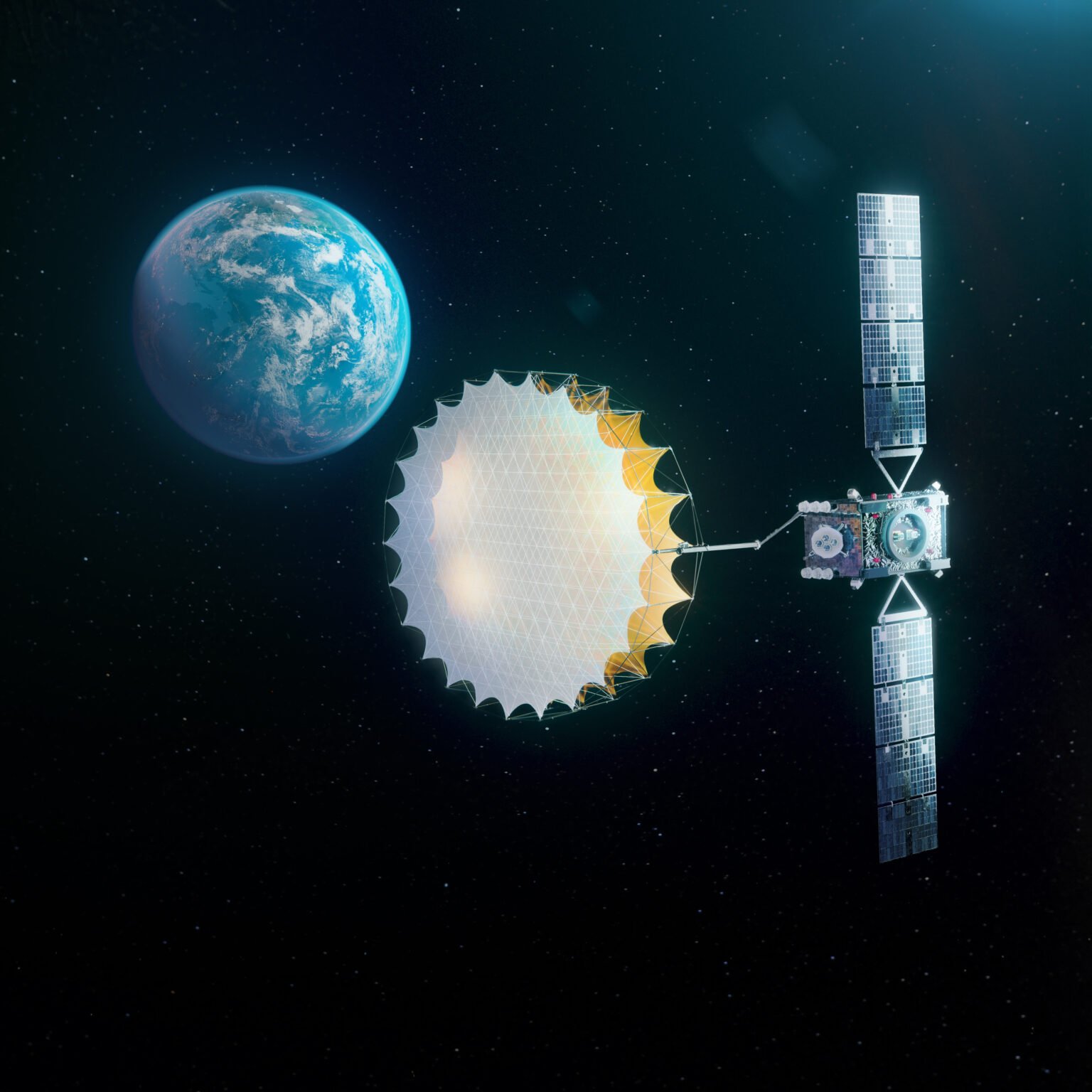

SWISSto12, founded in 2011 as a spin-off from Switzerland’s Federal Institute of Technology, was an early adopter of 3D printing for RF and antenna products. Over time, it expanded into complete satellite communications systems — user terminals for aircraft, ships, vehicles, and ground stations. Then came a bigger pivot: geostationary orbit.

GEO is the connectivity sweet spot — satellites appear fixed from Earth and cover vast areas — but historically it has been the domain of enormous, bespoke platforms with eye-watering price tags.

SWISSto12’s answer was HummingSat, a compact, lower-cost GEO platform aimed at making that orbit commercially accessible.

ESA, de Rijk told me, has been part of the story for a decade.

“Every time we took a step forward — towards more integrated, complex products — ESA was there to co-fund developments and provide technical expertise,” he said.

“The most significant example is HummingSat. Building a geostationary satellite is a massive undertaking. ESA supported us with funding and assigned a team of around 20 people who are deeply involved on a daily basis.”

That support, he added, helped SWISSto12 win its first commercial satellite contracts — and he’s clear about how he views the relationship.

"We’ve always treated ESA as a partner. We work together on new technologies with the shared goal of bringing them to market.”

De Rijk also credits ESA with becoming more pragmatic about how different missions should be run.

“If you’re launching a deep-space mission, you only get one shot — so the process must be conservative,” he said.

“But for a low-cost CubeSat tech demo, you can move fast and take risks. ESA has done a good job of categorising missions and adapting accordingly. It’s no longer one-size-fits-all.”

Making space matter on Earth: sustainability and downstream demand

That idea — that space is increasingly about real-world outcomes — sits at the centre of Daniel Smith’s work.

Smith is a founding director of five space companies and Scotland’s first sector-specific Trade & Investment Envoy for Space.

Through comms and marketing intelligence agency AstroAgency, he has worked with ESA on space sustainability and downstream applications. AstroAgency was the first UK commercial space company to sign ESA’s Statement for a Responsible Space Sector, and later partnered with ESA’s Space Sustainability team after delivering Scotland’s Space Sustainability Roadmap. For Smith, ESA’s influence is often most powerful in the “non-funding” category: convening, credibility, and doors opening.

“Initiatives like the Responsible Space Statement open doors, promote best practice, and engage key stakeholders — including other space agencies,” he said.

“ESA helps remove barriers to entry and supports commercialisation, not just for space companies, but for adjacent industries and society more broadly.”

AstroAgency’s mission is to shift how the sector talks about itself.

“We’re shifting perceptions away from deep-space exploration and towards Earth observation and satellite data applications — in maritime, agriculture, energy, forestry, finance, and conservation.”

The company has supported more than 20 Earth observation businesses across ESA member states, helping them translate technical capability into language that makes sense to non-space buyers.

“Often, that means leading with end-user benefits — and only later mentioning that the data comes from space,” Smith said. And in his view, that downstream market is where the real growth is. “ESA has a critical role in pushing this narrative forward,” he said.

“With the geopolitical climate and the importance of Earth observation for defence — particularly since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — ESA’s ability to catalyse collaboration across member states has never been more essential.”

ESA as enabler — and as an anchor customer for data

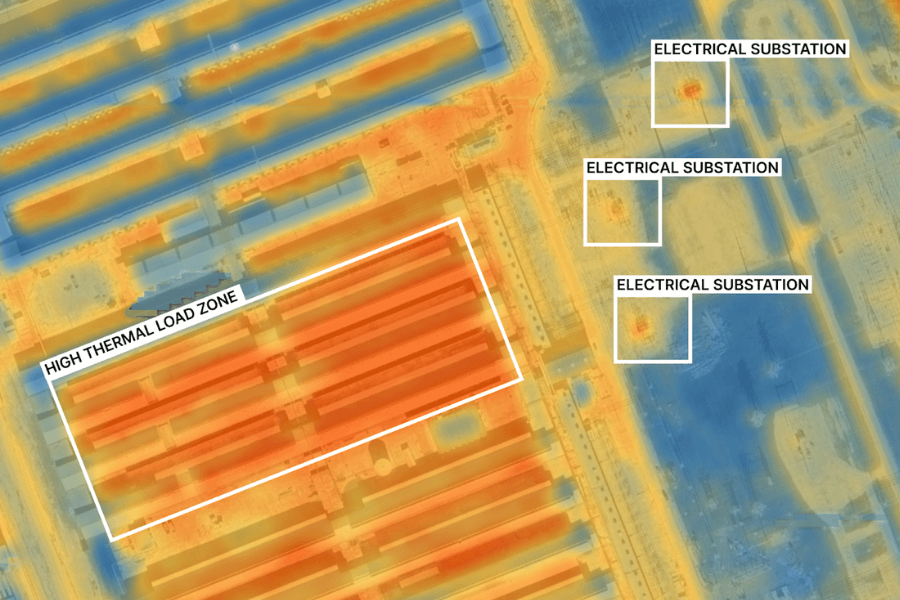

A similar point comes through from James O’Connor, Head of Imagery at SatelliteVu (SatVu) After HotSat-1 launched, ESA ran a data evaluation exercise to validate the accuracy of the pipeline, and later purchased archive imagery to make freely available to researchers through an announcement of opportunity.

From O’Connor’s perspective, ESA has increasingly signalled that it wants to be part of enabling commercial EO providers — including through anchor-style contracts.

“Programs like Copernicus Contributing Missions and Third Party Missions show real commitment to enabling commercial data providers,” he said, although he noted decision-making can still feel opaque or slow.

He credited ESA Director General Josef Aschbacher with cutting the time from announcement to award, and wants to see commercialisation become more explicit alongside science.

“ESA member states have world-class talent in Earth observation. Identifying commercialisation targets that complement Copernicus should be front and centre — so applications like disaster response are fully covered beyond the Sentinel missions.”

Launch is different: risk, tempo, and the need for early demand. If “anchor customer” matters in data, it’s even more existential in launch.

Stella Guillen, Chief Commercial Officer at Isar Aerospace, argues that ESA support is important — but the mechanism has to match the market.

“ESA’s support can be crucial for startups entering the market and scaling,” she said.

“But negotiations around funding, programmes, and service agreements need to keep pace with commercial realities.”

Isar Aerospace, founded in 2018 as a Technical University of Munich spin-off provides cost-efficient, flexible launch services for small and medium satellites and constellations. For Guillen, ESA’s most valuable role would be to take early, calculated risk as a customer.

“Acting as an anchor customer — willing to accept higher risk in early maturation phases — is especially important for launch companies,” she said.“It helps us build credibility with other stakeholders.”

And she’s blunt about where leverage sits for emerging players.

“Funding has traditionally focused on technology development. But for companies like ours, the biggest lever is customer agreements.”

Space traffic management: credibility, validation, and a faster ESA

As orbit gets more crowded, OKAPI:Orbits sits in the infrastructure layer of the space economy: the tools that help keep satellites safe and space usable. Founded in 2018, the company uses AI-driven data fusion to predict and manage orbital risks — from collision avoidance to interference.

CEO Kristina Nikolaus said ESA has played a meaningful role in both development and validation through ESA BIC, the General Support Technology Programme (GSTP), and ESA COSMIC (Competitiveness). “The processes are generally clear and transparent,” she said.

That support comes amid a step change in ESA’s overall ambition. In November, ESA Member States committed a record-breaking €22.1 billion in funding, significantly expanding Europe’s space technology agenda. Central to this is the enlarged GSTP, which secured around €5 billion for technology development — a 70 per cent increase on the previous cycle — spanning everything from early-stage research to in-orbit demonstration. The programme also introduced a new Resilience and Security Component, reinforcing Europe’s focus on sovereignty and operational robustness.

“GSTP can be slow — that’s expected — but COSMIC was significantly faster,” Nikolaus explained.

Coordination can be a headache, Nikolaus noted, with multiple points of contact across ESA and national agencies — but the credibility payoff is real. “ESA contracts helped us build trust in the industry,” she said.

“COSMIC allowed us to benchmark against ESA standards and publish our results, which were very positive.” She also sees ESA evolving.

“Newer programmes like COSMIC show a real shift towards agility,” Nikolaus said.

“For companies operating in the institutional space sector, ESA engagement remains a strong asset."

Inside ESA: sovereignty, fragmentation, and learning from New Space

From within ESA, Polyzois Kokkonis, Future Programs Officer frames the agency’s role in terms of sovereignty — not only ownership, but capability.

“A country may not own satellites outright, but it must be able to build and maintain them. ESA focuses on ensuring European industry has that capability.”

He also pointed to the growing “democratisation” of space, driven by New Space trends such as smaller satellites, cheaper launches, and commercial off-the-shelf components.

“This makes space more accessible, creating new opportunities for startups and smaller nations.”

But he also flags Europe’s structural disadvantage: fragmentation. “The US benefits from a unified market and consistent regulation,” he said.

“Europe doesn’t — which makes scaling harder.” However he contends that the learning curve has shifted in Europe’s favour.

“Reusable rockets are now proven, for example. That reduces uncertainty. Europe can learn from those who went first, adapt to its own needs, and move faster.

At ESA, the job is to hold all the pieces together — launch, satellites, ground, data — while ensuring Europe can compete in a space economy no longer defined solely by institutions."

At 50, the European Space Agency as an organisation characterised towards impact on Earth, commercial enablement, and strategic resilience. Whether helping companies climb the value chain, acting as a first customer for data and services, or translating space capabilities into downstream applications that matter to non-space users, ESA has become a critical bridge between public ambition and commercial reality.

At the same time, geopolitics has sharpened ESA’s role in resilience and security. Space is now critical infrastructure, underpinning climate monitoring, crisis response, defence, connectivity, and economic stability. The scale-up of programmes like GSTP, the creation of dedicated resilience and security components, and faster, more agile mechanisms such as COSMIC reflect a clear shift: Europe is no longer just investing in space excellence, but in space capability as sovereignty.

ifty years on, ESA’s relevance is not just intact; it is increasingly grounded — in Earth’s needs, Europe’s competitiveness, and the security of the space environment itself.

Image: Europe at night from space. Photo: ESA.

Would you like to write the first comment?

Login to post comments