Editor’s note: This interview has been recorded and published as part of a content project in collaboration with the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO).

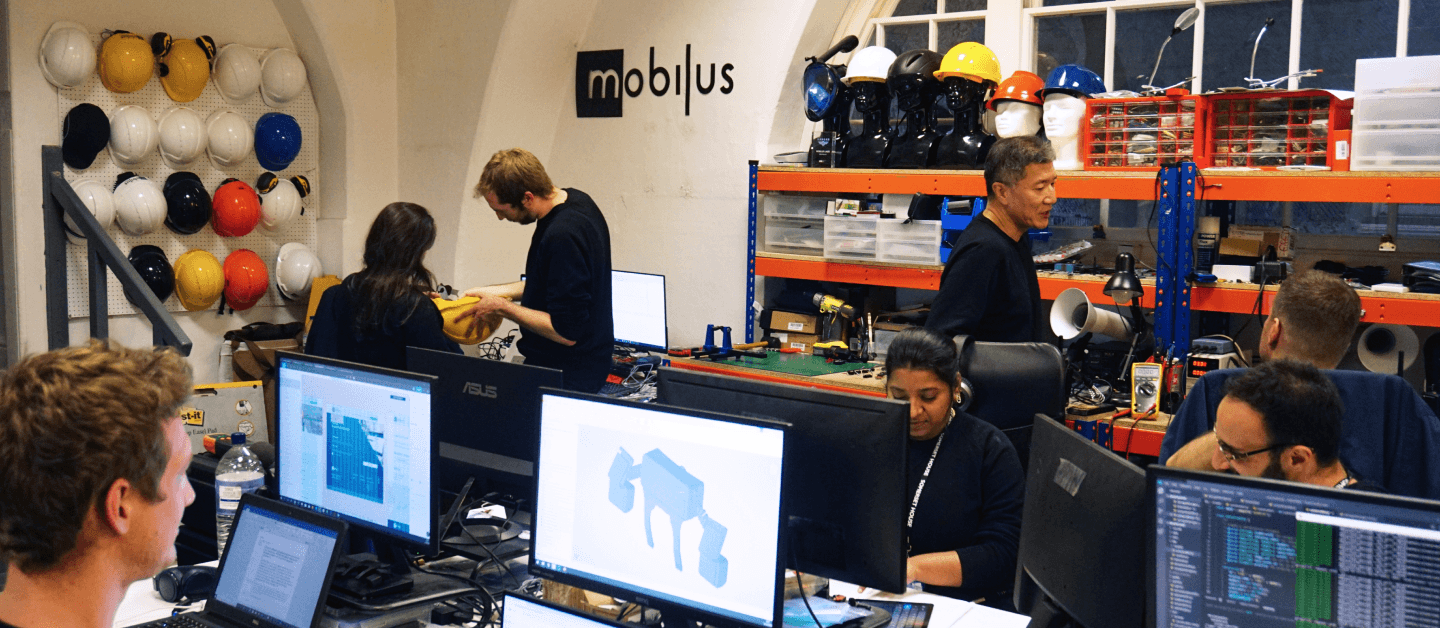

Jordan McRae is an engineer and inventor, who founded Mobilus Labs after a diving accident, in which he was unable to communicate with his teammates underwater. Using the phenomenon of bone conduction, Mobilus products work as wireless headsets that are suitable for extremely noisy environments. We sat down with Jordan to learn more about himself and the company he’s founded.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Q: Tell me more about Mobilus Labs.

A: Mobilus Labs has a general mission of removing friction from the voice communication experience. There are two paradigms that we're moving away from or undoing: one in the hardware, and one in the software.

The hardware paradigm is a pretty old one, it's about 150 years old. Since the invention of the phone, you always have a device stuck to the side of your year and something in front of your mouth — the headphone and the microphone. Our point in moving away from this paradigm is that although the device now has changed incredibly, it's a supercomputer, but for the phone or voice, experience hasn't changed really much at all.

The second paradigm is what we're actually doing right now, as we're dialling in to speak with each other. It's this sort of software teleconference room paradigm where there's this virtual room somewhere on a server that gets created, we all dial in to that virtual number, and we have a conversation. We're isolated to this virtual room, and then when that conversation is over, the room eventually disappears. That works really well if you're focused on the remote meeting room paradigm; it doesn't work very well if you're trying to use that same voice experience for someone out in the field or for distributed teams that are grouped in various ways. They are working dynamically in different environments and have to jump in and out of those different conversations.

Jordan McRae

Jordan McRae

We look at both those paradigms and say that the overall experience can be drastically improved by removing friction across the board. So that's what we do, we build a wearable voice device called the mobiWAN. Our first product instance is for the industrial sector and integrates into safety helmets. The wearable allows to receive and transmit voice through the bone conduction technology. We've developed something called a two-way bone conduction technology, so vibrations on the back of the user’s head allow that audio to be transmitted directly to their inner ear.

The key aspect of what we're doing as well is that it also works in the reverse direction, we use the “speakers” as the microphones to capture the vibrations in your face and your skull. That gives us some really interesting advantages with respect to noise cancellation and voice isolation.

On the software side, we're attacking the traditional paradigm by creating something more fluid where you have persistent channels that you can create and organize your team to stay within. It's all based off of the voice experience. We've decoupled the listener and talker mode of our conversation so you can listen in to multiple conversations at the same time, and then you talk into one of those conversations. Because that system is cloud-based, it allows us to bring in a whole bunch of other digital features like voice recording, search, voice recognition, and transcription. It allows us to interface with other devices that are voice-enabled, so it's not just human-to-human communication, but also getting alerts in real time from different sensors or cueing different voice-enabled AI platforms.

Q: How many customers do you have now?

A: We have four key organizations that we're focused on today, and we've limited to that just to make sure that we can demonstrate that the product is working in these various sectors. With those four organisations we're operating across construction, utilities, and energy. Our biggest customer was just announced recently, it's called Trimble, they've placed the first order of thousands of units that we shipped earlier this year; their end customers are all the big names in oil and gas, and manufacturing, and things like that. We're just starting to get a lot of feedback from people out in the field — more than we have had over the last years with our first customers, which were primarily in the construction industry.

Q: What was your background before you founded the company?

A: I'm a technical founder, my background is in ocean and space robotics. The origin story behind Mobilus is actually related to a near-death accident that I had in Africa, diving off the coast of Mozambique. It shook me up, and I had to think, well, that was pretty scary, do I really want to do this activity? But also, as a stubborn MIT engineer, I thought that there has to be a solution to this. And that sent me down this path of finding a technical solution for voice communication in an extreme environment.

At that time, my extreme environment of choice was underwater. As I developed that solution and started showing it to people — that's when we had that epiphany that the problem we'd been solving was way more ambitious than just scuba divers communicating. It was about removing friction from the voice experience in general. And it just so happens that extreme environments like underwater, or a construction site, or a factory, are the ones that test those friction points the most. That, and the commercial attractiveness, is the reason why we focused on the industrial sector first.

Q: So that's the big vision here? Are you planning to bring the technology to customers outside the industrial sector?

A: The global vision for Mobilus is sticking to that general idea of removing friction from voice communication, wherever it is. We're starting in industrial sector with a B2B business model. This can take as far as B2C: you know, I want my mom and my brother using this — and they're certainly not construction workers, but they are individuals that operate within various teams.

I don't want to just say that we're going to go all the way and easily compete with some of the amazing audio products on the market today. It's tricky to serve the consumer market where there are really good audio products already. Some of the challenges come from a design perspective, like battery power, battery efficiency, style and beauty… If you ask to put anything on someone's head, you're asking a lot. So, it's got to be very, very stylish. These are some of the things that I think we will conquer with time, but we wanted to start out focusing on core performance. With our design approach, we currently have all the real estate we need for a larger battery, so you have a full day's worth of charge.

Absolutely, my dream is that in the future a Mobilus device would sit on your nightstand. You wake up in the morning, you stick it behind your ear, and it just sits there the whole day — invisible, but it's giving you this kind of technological telepathy experience. Throughout the day, you switch different teams: one team may be your family, another team may be your friends for an afterwork dinner or drinks, and another team is your actual team at work as you're communicating amongst those various groups.

Q: How is your tech different from some of the devices already available on the market?

A: Bone conduction is a biological phenomenon, which almost everyone has been experiencing from the day that they were born. We don't hear our own voice just because it's coming out of our mouth into our ears. It's actually going as a vibration through our jaws, into our skull, into our inner ear. We're just using technology to benefit from and take advantage of that biological phenomenon.

So, where do we set ourselves apart from existing solutions? Most solutions you'll find on the market today are related to one-way audio streaming products. Some of the best ones that people are most aware of are primarily used by athletes as jogging headphones that you put in front of your ear. It actually looks like regular headphones; it just sits in front of your ear and vibrates in your temple. The key advantage of those products is that you can listen to music while running, but your ears are open, so it's a little bit safer and more comfortable. Some of them do have microphones integrated, so you can do a phone call if you want to — but it's a completely normal microphone, so you're going to get all the sound that comes along with whatever environment you're in.

Our system uses two-way vibration technology, so we're picking up the vibration from your face and from your head. And that, again, has advantages in noisy environments. We're also the only product using this technology that's fit for purpose in the industrial sector.

Q: How much does it cost?

A: We are a subscription-based platform. The price target is two tiers of subscriptions; there's one tier that's software-only, which means you're probably in an office somewhere in front of a computer or using your smartphone, and you don't have a helmet on all the time. You can communicate with a team that is in the field through the same software on your personal device, and that costs roughly £25 per month per user. And then we have a subscription that includes the hardware, and that's roughly £40 per month per user. With that plan, we're going to replace the hardware every two years.

Q: Let's talk about you as an entrepreneur. What was your entrepreneurial journey like?

A: It's been amazing. I was in San Francisco after working with Lockheed Martin for a small period of time, and started my first company — it was an invention firm. A colleague from MIT and I started collaborating on a wind energy technology and immediately moved to Hong Kong, where I'd spent about two years, and that's where I got my manufacturing chops.

I loved Hong Kong, and I still do; but for the next step of my journey I moved to France and set up an invention firm. I wanted to have the access to and stimulation from a huge diversity of different backgrounds — science, technology, and art. I also wanted to learn another language and engage with other people around the world, like Africa; also, I was looking for proof that invention could be done anywhere. In fact, the more constraints you have, even though it makes it more difficult, the more elegant your solution may be at the end.

One of the reasons why I was very happy to start Mobilus were these very strong constraints of the underwater world. I wouldn't have needed to move to something like bone conduction if I hadn't started that way; bone conduction was specifically looked at because you can't put anything in your ears when you're diving, you need to be able to equalise as you go up and down. And so it gave me permission to ask this question — if I can't use my ears, how am I going to hear?

I spent about 10 years of my life with my invention notebook, just putting ideas in, and they would bubble up to the top and I'd be working on two or three of them at any given time. Mobilus ended up being one of the consistent ones that stayed at the top of that list. And the more traction I got on it, the more I realised that an additional evolution would be required, which put an end to my romantic inventor days and started the innovation phase.

The fundamental insight that I had was that if I wanted to scale this the way that I did, I couldn't be one or two-person team anymore. I needed a larger team, and to get that larger team quickly, I needed money. Therefore, it was a very easy process for me to figure out that this needs to be a VC backable business. In our case, the VC model was a good fit for us, so we raised our first round of investment of £1 million and some governmental grants in the UK.

Q: Was it difficult for you to raise money?

A: Yes, it's difficult to raise money. I don't know why people would tell you all these stories that they're just walking in, and then cash is thrown out there. I don't know a single one of those. It's difficult to raise money, also because we're not your typical SaaS, we have hardware, so already there are some investors that are eliminated from our pool.

Having the American background, I find European investors a little bit more risk-averse, which is good and bad. It's bad only in the sense that that money comes slower, you have to answer a lot more questions, you have to have a lot more of a mature business before you get access to those funds. But it’s good in the sense that it's probably great that you're a more mature business before you get access to the funds, because it's hopefully eliminating a lot of waste. I try not to be too bitter about it, but it's not easy. It's a lot of rejection; I never was very good at rejection before — but I'm really, really good at it now.

Raising money is only made easy by conviction. It can be frustrating and tiring at times, and it can be exciting as well. As a tech entrepreneur, I've become more of a salesman and a fundraiser by necessity than by desire. I didn't go to school to do this. But it's a necessity to get this product and this technology in the world. It's probably particularly frustrating for someone with my background, but you just have to remember why you're doing it, what it will give you, and how important it is.

Would you like to write the first comment?

Login to post comments