1.7 million people who aren’t formally registered as visually impaired, but still suffer from sight loss severe enough to affect their daily lives. While services such as Be My Eyes – an app which connects blind and low-vision users with sighted volunteers and companies, through live video and AI to tackle the inaccessible parts of everyday life – do a stellar job in providing support for blind and low-vision people, there is always room for more, especially in real-time, hurried scenarios such as navigating public transport.

Many people in the UK struggle to navigate public transport because they simply can’t read the signage.

Zooming in with a smartphone only distorts the text further, while mainstream transit apps often lag or fail to capture real-time updates. The result? Missed buses, wrong trains, the risk of getting stranded and dependence on strangers.

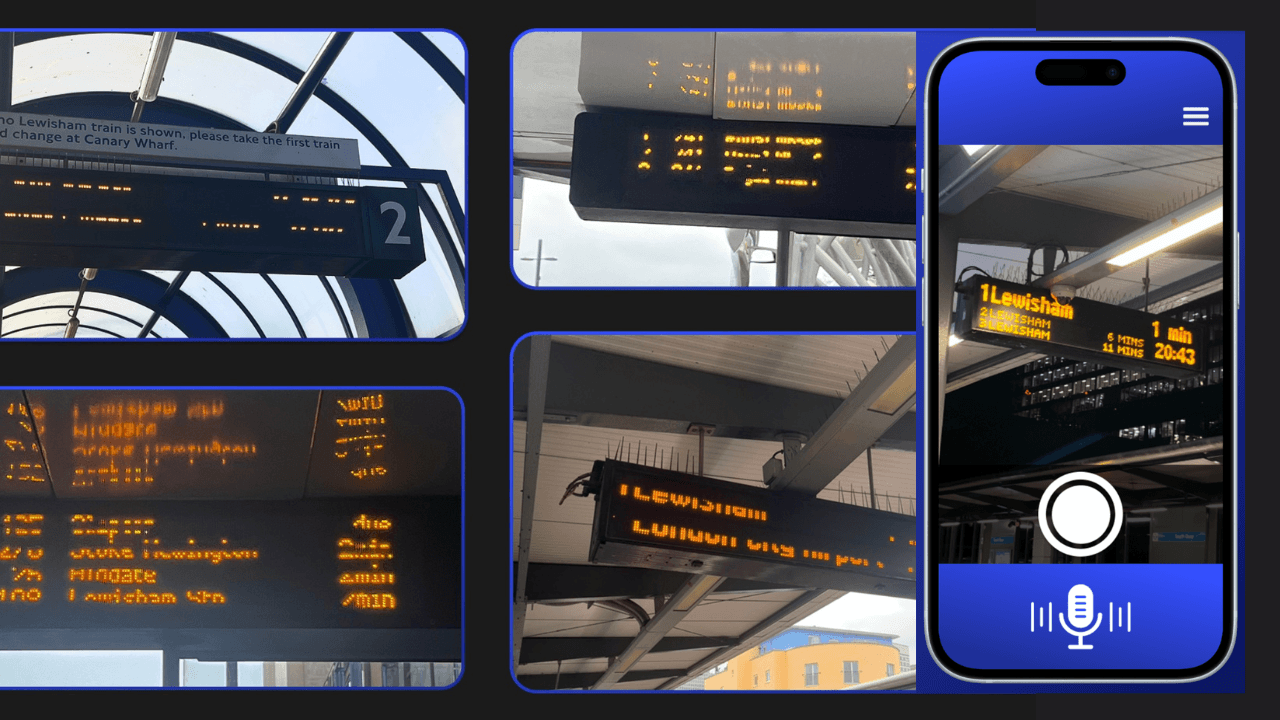

But now there’s a solution. Founded in March by UCL students, Solora has developed the RideOnTime app, which uses AI to translate transport signage into clear visuals—and audio if desired—in real time, offering people with sight loss a dramatically easier way to navigate bus and train stations.

Despite being in the thick of his dissertation in Human-Computer Interaction, CEO Jun Bak was kind enough to offer some insights into the solution and the company behind it.

From academia to an app store

Bak has a background of around a decade in UX design and digital strategy, with deep experience in user experience, conversion optimisation, and product strategy across in-house and agency roles. More recently, he completed a Master’s in Human-Computer Interaction at UCL.

During the course, he met four classmates, and together they worked on a disability interaction module, co-designing an application with a visually impaired user, which eventually became Solora. The technology is both simple and powerful. The app detects the signboard using AI.

“Then, we adjust technical factors like shutter speed and exposure to reduce distortion," explained Bak.

“Combined with additional coding and AI enhancements, we’re able to “fix” the display so users can clearly read the information. We’ve gone through several rounds of testing, and the results have been very positive.”

UX-testing with those with lived experience

I was curious about the UX testing, as I’ve unfortunately met a robotic wheelchair startup that only tested its tech in able-bodied people and a smart home platform for blind and low-vision people, which was only put forward for testing weeks before its launch.

According to Bak, the team was fortunate that the project began as part of a disability interaction module, which allowed them to co-design the solution directly with a visually impaired user living with Stargardt disease.

“By learning about her daily transit challenges, we identified LED signboards as a major issue.”

For broader testing, Solora collaborated with Vision Ability, a nonprofit in East London.

“We hosted a workshop with about 20 visually impaired users, took them to a station, and allowed them to try the app in real-world situations. Their feedback was overwhelmingly positive.

Some participants told us they were just beginning to travel independently, and that this was one of their biggest frustrations.”

Solora launched on the UK App Store as a pilot and now has about 50 active users.

“We’re continuously monitoring performance through analytics and recordings to measure accuracy and optimise further,” explained Bak.

Why mainstream transit apps and support services aren’t enough

In the UK, disability rights in public transport are primarily protected under the Equality Act 2010 and the Public Service Vehicles Accessibility Regulations, which require transport providers to make reasonable adjustments, so I was curious why public transport authorities weren’t doing more about the problem.

According to Bak:

“Quite rightly, there is extensive guidance and regulation concerning the level of support that should be offered to sight-impaired and severely sight-impaired people on our transport network.

And visual cues, such as a guide dog or mobility cane, mean it can be easier for passenger assistants to proactively identify when a sight-impaired or severely sight-impaired individual may require additional help in a bus or train station.

But there is a massive group of underserved people in the UK who suffer from varying degrees of sight loss.

We know that individuals with different forms of sight loss find it difficult to navigate the transport network, but for a number of reasons, they may be reluctant to ask for assistance."

Further, some larger authorities may be aware of the specific challenge with the signage, but they often assume that having a live feed solves it.

“The issue is that LED signboards display the most accurate, real-time information — based on the actual movement of buses and trains.

Apps may lag or require multiple steps to check timetables, but with RideOnTime, users can just point their camera and instantly get the information.”

Solora has already been recognised with awards, including Most Inclusive Product at UCL’s latest Venture Builder Programme and the SustainTech Pitching Competition, winning £1,500 and £1,000, respectively. Now its applying to UCL’s Hatchery program, which supports spin-off startups over two years.”

In terms of business model, the app will always be free for visually impaired users. Long term, Solora is looking at white-labeling — integrating its solution into existing platforms run by transit authorities. According to Bak, the current UK launch is essentially a pilot to gather data, prove impact, and run focus groups.

“We’re already in conversations with transport authorities about integration, and we’re actively seeking our first client.”

The team is also exploring EU mobility funding opportunities and ways to expand beyond the UK. However, the biggest challenge has been accommodating individuals with varying levels of vision loss — some people are severely visually impaired or blind, and they want to use the app too.

“We’re developing features like AI-guided detection: users can wave their phone, and the app will guide them with audio cues to point toward the signboard. This requires extensive testing with blind users, but it’s our next major step,” shared Bak.

Solora is proving that startups can tackle real-world problems when they put lived experience at the heart of design. By working directly with people across different levels of vision loss to shape and test new features, the team is building technology that doesn’t just work in theory — it genuinely meets the needs of those who rely on it every day. Its a valuable playbook for all social impact startups.

Would you like to write the first comment?

Login to post comments